Of the films shows hoping to pronounce some kind of truth about conflict in the Middle East, few are embraced by critics, and fewer by the public. They don’t make money, and only a select couple were embraced by critics. There’s Jarhead, which barely made back its budget despite Jake Gyllenhaal in the lead. Next, look to The Kingdom, which fell to a similar fate with Jamie Foxx. Green Zone was Matt Damon and Paul Greengrass’s very expensive follow-up to the Bourne series, finding a Bourne-like military man investigating weapons of mass destruction. It flopped hard. Not even resounding critical acclaim could save The Hurt Locker from being the lowest grossing best picture winner ever. There’s one exception, but due to its historical relevance and masterfully executed nature, Zero Dark Thirty is more an exception that proves the rule rather than an indication of change. So, in a way, it doesn’t belong with the others. But what of the others? There’s a key through line uniting each of them together. They are political failures. They either have too much to say or too little, unable to find a healthy middle ground and subsequently alienating audiences.

Lone Survivor is the latest offender, and it’s one of the worst.

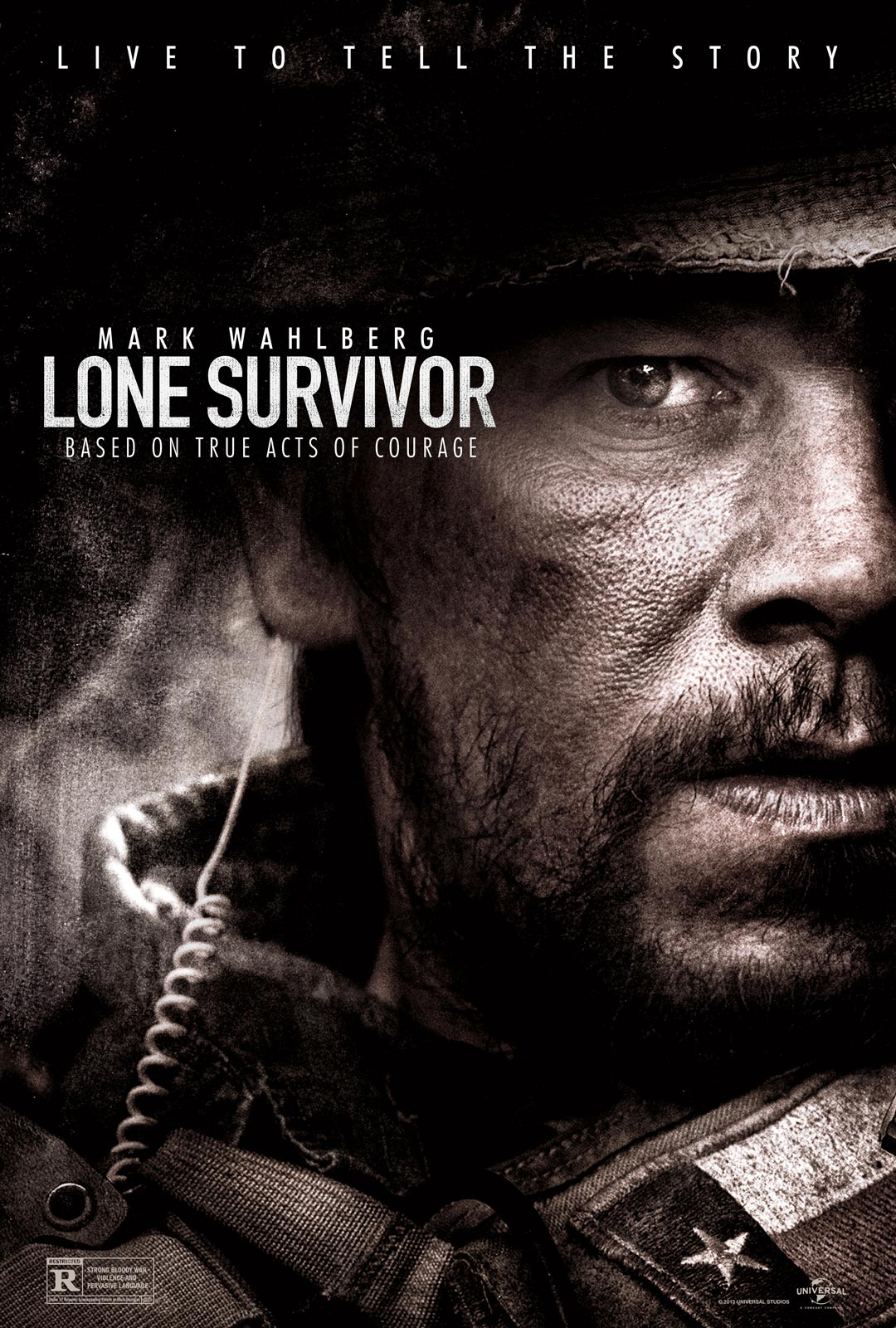

Peter Berg, who recently insulted audiences around the world with the exceedingly dim-witted board game adaptation Battleship, based his latest on the book Lone Survivor, of which the film took its name. The book and film chronicle a botched mission named “Operation Red Wings’ that took place during the War in Afghanistan (the book also documents the enlistment and training of its author, which the film has excised). Navy SEALs were sent to capture or kill an infamous Taliban leader but failed. Most of the squad ended up dead. The book dramatizes the mission with very little before or after, just enough time to introduce the four SEALs that lead the mission in-film. The cast is strong, one of the strongest points of the film, dutifully made up by Mark Wahlberg, Taylor Kitsch, Emile Hirsch, Ben Foster, and what amounts to a cameo role by Eric Bana. Although little time is spent characterizing any of them, the cast is extremely likable and imparts that trait onto the characters. We come to know and care about these guys after only being with them for ten minutes, and their chemistry thrives as the film continues. The script’s efforts to humanize them for the audience, such as ongoing mini-arcs that involve wall tiles or an Arabian horse, would’ve felt like the artificial contrivances that they are rather than endearing points of characterization. The characters work.

It was an interesting decision to embrace the public knowledge element of the story, and instead of playing which audience members know the ending, it’s flaunted openly at them. Flaunted, since, well, it’s in the title, but it’s also in the marketing. An extended five minute trailer played amidst the pre-screening advertisements, before the rest of the previews even, to ensure as many people as possible would be aware the mission failed and most of the men ended up dead. If you think that’s a spoiler, blame Peter Berg, not me. This creates an interesting scenario, where tension and suspense must be cultivated alternative to ‘what happens in the end.’ To be honest, it’s largely effective. The action is tautly directed and portrayed with startling realism and avoids shaky cam cliché. We see everything, more than many would probably like, but it’s by looking death in the face that we feel the physicality of the firefight. The geography of Afghanistan is used to remarkable effect, and it’s among the first films depicting battles overseas to give a palpable sense of how they’re probably carried out in this terrain. Whether that’s actually true or not isn’t important, that it feels true lends these sequences an unparalleled authenticity for action in rural Afghanistan. After the monotony of urban warfare popularized in war cinema by Saving Private Ryan and later Black Hawk Down, the drastic change in scenery, and thus how battles are fought, is a very welcome one. Soldiers delicately maneuver within the winding rock formations and rich forests, and although they can’t come close to matching the intensity of The Hurt Locker or Zero Dark Thirty, they’re convincing and intense. Lone Survivor is easy to invest in, or it would be, if the thematic undertones didn’t abrasively evolve into overtones and drown out everything else.

At best, the politics are confused. At worst, they’re plain contradictory. For starters, the first three and a half minutes of Lone Survivor literally plays as though it was an extended ad for the military. We see what appears to be stock footage of troops in training with a voice-over about how the military pushes you to achieve the full potential of your humanity and creates a lasting brotherhood. The war sequences themselves continue the propagandistic lathering of military love. The Navy SEALs churn down enemy combatants at the same rate as James Bond in the opening airport scene in Tomorrow Never Dies, and, despite all their visceral realism, the war sequences thus become a cartoon. Massive death tolls are dealt out without apprehension or care, behavior that’s forgiven by the opening voiceover that describes why they fight “where the bad things live, where the bad things fight.” The V.O. ostensibly hopes to demonize the Taliban combatants to the extent that audiences will cheer oorah with every subsequent brutal kill, many of them headshots with significant blood splatter.

Had the film been directed by Michael Cimino, these moments would have a resolute moral ambiguity surrounding them rather than the fist pumping they seem to now. However, these men were sent into an enemy combat zone unprepared and with ill-suited equipment. Their first stop was a mountain overlooking a town, and it was such a poorly chosen vantage point that they had to relocate entirely. That decision caused them to run into farmers, and the operation was then compromised. There’s a pervading sense over much of the film that, in general, it was a badly planned op with many uncalculated risks. The mission fails, and for their mistakes, the mistakes of their superior officers, and, if one was to extrapolate further, the mistakes of their country, the Navy SEALs are brutally killed. This isn’t a story of heroism but a story of institutional and military failure where, despite their earnest intentions and highly trained skills, the best they could do was not die sooner. Taken on these grounds alone, a stark anti-war message emerges that condemns the entire hierarchy of U.S. military command. But the film doesn’t end there. It ends with a sweeping photo montage of the real life soldiers involved in the Operation Red Wings, played to the tune of Peter Gabriel’s 2010 cover of David Bowie’s famous song Heroes. By framing clearly anti-war content with a flag waving start and finish, the film concludes as a garbled mishmash of loud voices trying to consume the other. Lone Survivor is at war with itself as much as the Navy SEALs are with the Taliban, leaving the end product an impotent and empty vessel of U.S. nationalism.

C-