Since Woody’s Allen’s illustrious film career began in the mid ‘60s with What’s Up, Tiger Lily?, he’s pushed to release one film per year. Good, bad, or so-so, a film gets made. Amazingly, there are only seven exceptions: 1967, ‘68, ‘70, ‘74, ‘75, ‘76, and ‘81. As such, evaluating his filmography as an ongoing phenomena defies comparison to any other filmmaker, living or dead. Knowing him, or at the very least his persona both on screen and off, that must please him. Take, for instance, how if he has a stinker one year and an okay picture the next, if the third year’s release is a stormer, all is forgiven: “The best picture made in years!” “Return to form for Woody!” His filmmaking methodology enables him to experience a creative liberation that surely must make rival filmmakers jealous, especially those stuck in the mud as a studio director-for-hire. If he has an idea, he writes it and he shoots it. It’s that simple. If it doesn’t work, he moves on. He’s good enough a filmmaker that it almost always only takes a few tries before he’s uncovered cinematic gold. And, more often than not, it’s of the variety only he is capable of finding.

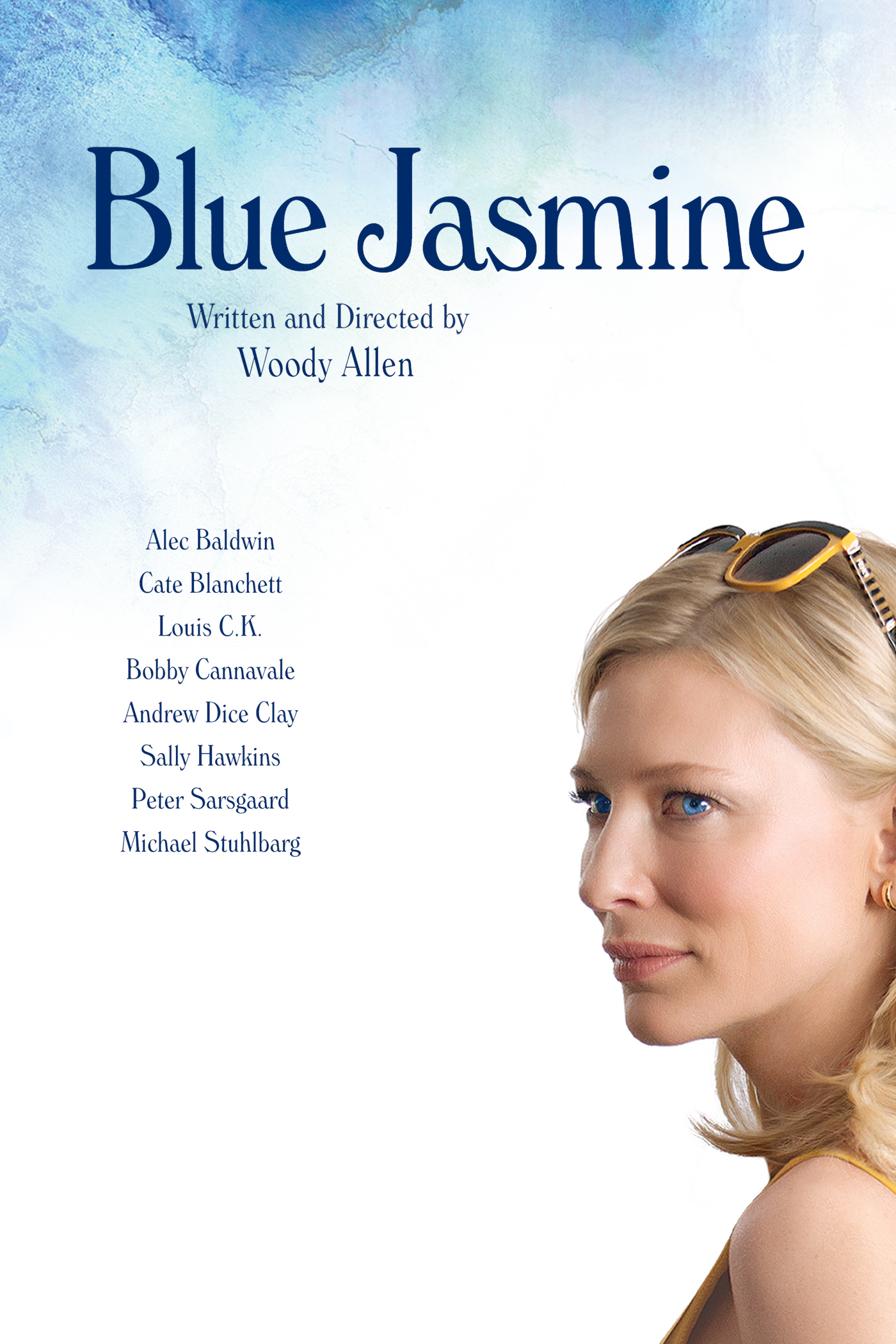

This has never been truer than his latest, Blue Jasmine, which, simultaneously, could only have been made by Allen while also being boldly unlike anything from his previous work. At the incredible age of 78, the endurance of all his faculties— physically, mentally, and creatively— is nothing short of amazing. More than amazing, for Blue Jasmine, it was necessary. Jasmine is one of his more demanding features yet, a film more comically serious than seriously comical. This is to my pleasure, and although subject matter is unusually stiff-faced, the punch line isn’t ever far away. Allen uses the tone as a necessary tool to tackle everything from the 1% vs 99%, gender, and the artificiality of today’s world. Not all original subjects for the slapstick existentialist, but few of his films have explored them with such delicate grace. It’s a tricky balance to master, and for my money, he does beautifully. Jasmine Francis (the title character) is introduced in media res fleeing Manhattan. She’s broke and nearly totally alone, journeying to stay with her sister Ginger in San Francisco. She was a Park Avenue socialite, with a house in the Hamptons and an exceedingly wealthy husband, played with slimy delight by Alec Baldwin. If it sounds too good to be true, it was. It all collapsed, and her mind with it. She’s fixed herself a medical regimen of pill popping and alcohol, and the whole film sees her on the cusp of mental breakdown.

Jasmine is only the latest in a long career of powerful female characters, and, as played by Cate Blanchett, might be the best. Let me say it upfront: her performance is a knockout. She’s tremendous, and every bit of acclaim she’s received, and surely will continue to, couldn’t have been more earned. The accent, her body language, the nuanced fragility of her voice, these are all the makings of a best actress win. She probably will win, too. Blanchett nails who Jasmine was and brings together many underlying themes of the piece with her performance. Jasmine is narcissistic, manipulative, pretentious, and compulsively uncaring to anyone around her. That is, to anyone who doesn't serve her goals in life. On paper, she’s unlikable. Most actresses would play her as unlikeable. How couldn’t they? Blanchett doesn’t. Jasmine has an artificial warmth easily mistaken for the real thing, which, along with a pent-up sophisticated aura she’s cultivated for herself, she’s a hot item for men. Her sister, Ginger, blames it on Jasmine getting all the good genes which mask her nasty interior self. One could say Jasmine’s entire character is an extended metaphor, or criticism, for the 1%, where men and women are born into prosperity and status without deserving it. They proceed to take what the “less fortunate” (genes, in the film’s case) can’t have, and thrive while others suffer. The entire narrative works on a similarly metaphoric level, and to flesh out these themes, Allen’s employed a tip top cast. Sally Hawkins plays Jasmine’s sister with the shining perseverance the role required. She has her own sort of status, but Jasmine can’t see it. Loved comedian Louis C.K. has what amounts to an extended cameo, and, unsurprisingly, he’s a lot of fun. The rest of the class, including Bobby Cannavale and Andrew Dice Clay, do sound work too.

To dramatize Jasmine’s frenetic mental state, her subjectivity plays an overwhelming role in the story arc of the film. As her mind is whisked away and wanders, so does the screenplay. In this way she not only overpowers the characters around her, but the actual film itself. I’m talking of course about the flashbacks throughout, which almost always seem to be active intrusions on her present day consciousness rather than a plain storytelling tool for context. Her flashbacks are out of order, occasionally misleading, and often meaningfully related to what she’s confronted with in her present life. This is a clever narrative device and serves multiple purposes at the same time. The audience is given exposition on her past, while keeping us in the dark just enough to cultivate suspense. Because of the tragic context with which we see them, the sunny smiles and thousand dollar handbags bear a bitter undertone. From an audience point of view, the interplay between present and past is reasonably complex and also dramatically compelling. It also gives Allen a chance to show off some of the tricks he has learned as a filmmaker over the years. The colors and sounds of one scene melt into the next with well-placed edits, and old school tricks like those give the film a sophistication younger filmmakers ought to study.

With his latest picture, it’s never been clearer, Allen’s on fire. Relevant, refined, and deeply emotional, Blue Jasmine is one of his best late-career films, and Blanchett is a sensation.

B+