Follow Brendan Hodges at

A safe movie by design, The Visit is suspense maestro M Night Shyamalan’s most watchable film in more than ten years. The justly prolific writer/director who got his start with the impressively assured ghost story The Sixth Sense—a classic—is nothing if not ambitious. His movies are full of ideas and on every level, playing with the conventions of style and plot like e a mad conductor and the various film departments his orchestra. (Almost) all of his movies have, if nothing else, isolated moments of brilliance and true movie making wonder, combining inspired uses of score, lighting, and composition to bring his visionary screenplays to life. That much is true, and you’ll find nary a naysayer to that effect. But that same sense of invention is what pushed him to the breaking point of indulgence, leading to masturbatory trash in the way of Lady in the Water, The Happening, The Last Airbender, and After Earth, and many have been hoping for the sweet nectar of career resurgence.

The Visit is not the answer to Shyamalan’s problems as an artist, or the long-wanted apology for his fans. Exactly what made him fun to watch is missing, seemingly taking a palette cleanser approach (like Michael Bay did with Pain and Gain after a bunch of Transformers movies). Instead of the convoluted plot and in-your-face symbols of a movie like The Village, which preposterously pondered a theme of hardcore isolationism, The Visit is a stripped down boxcar of a movie and that creative choice is the source of all the film’s virtues and all of its sins. Its simplified premise is purposeful and effective but never revelatory, and ultimately, to continue my metaphor, by the nature of itself can’t accelerate to full speed. But you do have fun.

This is, in fact, a found footage movie. It’s something the marketing didn’t explicitly tell us, and Shyamalan subtly reinvents that horror subgenre in a somewhat creative way. You find out within minutes that The Visit isn’t so much found footage as much as finished footage. The movie is actually the finished documentary of one of the characters, a 15 year old girl named Becca (Olivia Dejonge), and (too) much time is spent mulling over the specifics of film aesthetics, mise-en-scene, and characters talking about camera setups. The gimmick wears out its welcome but gets points for trying something new, proving once again why horror has long been a surprisingly fertile ground for experimentation.

The Finished Footage aesthetic pays off in some ways more than others, especially in an early scene where the characters play hide and seek under a house, leading to the year’s best jump scare since It Follows. Most of my theater jumped, shrieked, and even I admit to feeling shivers tingle down my spine. Jump scares are an old trick, but the execution is atypical, and the artificial spontaneity of Finished Footage is played more for suspense than straight up scares (despite this example). With the documentary already ‘completed’ the film asks how the kids made it out or if someone else appropriated the footage and made it into something else, like Werner Herzog with Grizzly Man (about the life and death of Timothy Treadwell and his girlfriend Aimie, using footage Treadwell filmed for personal use to construct his documentary with his iconic voiceover of existential observation). The smartest thing about The Visit is how it follows the old tropes of teen-friendly horror movies but executes them with an extra ounce of sophistication. Long a disciple from the church of Hitchcock, Shyamalan once again summons suspense out of thin air, and he does it often. All the more impressive is how he accomplishes this without a film score of any kind.

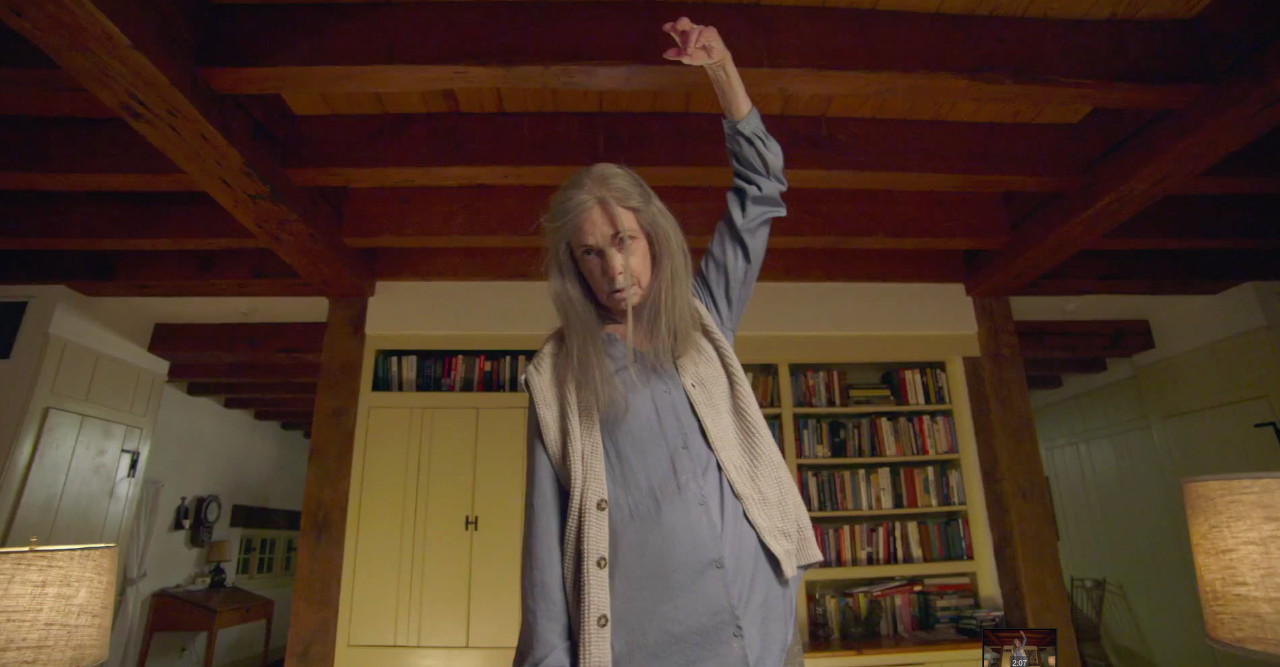

Aesthetic hoopla aside, the story is unusually common for a director known for dreamy strangeness. Becca and her eight year old brother (Ed Exenbould) are spending a week with their grandparents—Nana (Deanna Dunagan) and Pop Pop (Peter McRobbie). Who, we quickly find out in an on-camera ‘interview’ with the sibling’s mom (an enlivened Karthryn Hahn) had a falling out with her parents around 20 years before and refuses to talk about it. That’s the first ‘mystery’ of many that Shyamalan plants for us to try and figure out, and some reveals are more satisfying than others. What follows is the weirdest week of their lives: the grandparents are at best unstable or at worst crazy. Grandma goes from making delicious cookies and being a cheerful, warm, maternal presence to making what sound like threats. In one scene featured in most of the marketing, the grandma eerily asks Becca to clean inside a large oven. All the way inside.

The script plays off the strange behavior of just about everybody’s grandparents but ups it to lethal extremes, and you’re unsure of what’s dangerous and what’s dementia. In the same off-color way The Village uses mental illness for a cheap twist, The Visit suggests that the line between being old and being a psychopath is a strangely thin one. Moreover, mental illness plays a role in the film and there’s something lurid in exploiting a serious disease for the purpose of pulp. But that’s for another article.

While there’s red herrings and a prolonged predictability at work (I saw most of the movie coming early on), what I didn’t guess was how laugh out loud funny The Visit consistently is. Neither a satire or straight faced horror, the tipping between both tones is a level of nuance I didn’t think Shyamalan was capable of anymore. Tyler (the brother) is a wanna-be gangsta rapper, and his raps littered throughout the movie are as terrible as they hilarious. And unlike every facial expression by Mark Walhberg in The Happening, laughter is an intentional part of the movie. The prolific director discovered one of his late-career talents—his ability to inspire laughs—and he plays to that strength with a resolved self awareness that’s a pleasant surprise. Pitting humor and suspense together are a fetching pair, and the contrast works. Well-tuned performances guide the ship, and deftly handling the two tones is particularly impressive for Dejonge and Exenbould, given their young age.

One consideration is that had The Visit come out with an unknown director’s name in the credits, and not Shyamalan’s, and therefore no fanfare, this would be remarked on as a promising start instead of a positive upswing on a crashing plane. It’s in a high class of its low brow genre, but sadly never becomes the sum of its sometimes very good parts. Shyamalan ultimately fights against himself, knocking down his victories with stilted dialogue or unnecessary scenes that undermine the tension and pace. The biggest problem isn’t that it’s terrible, but that it can’t stay being very good for very long. There are lulls. But there are victories too, so even if The Visit never comes alive as a result of the uneven assembly, it’s a mostly worthwhile entry in his previously dying catalogue. When the heavy handed ending reveals The Visit’s thesis as a plea for forgiveness and even redemption, something the characters in the movie call an “elixir”, you wonder if Shyamalan hoped The Visit would be an elixir of his own. It’s not, but it is a start.

C+

Follow Brendan Hodges at