Follow Brendan Hodges at

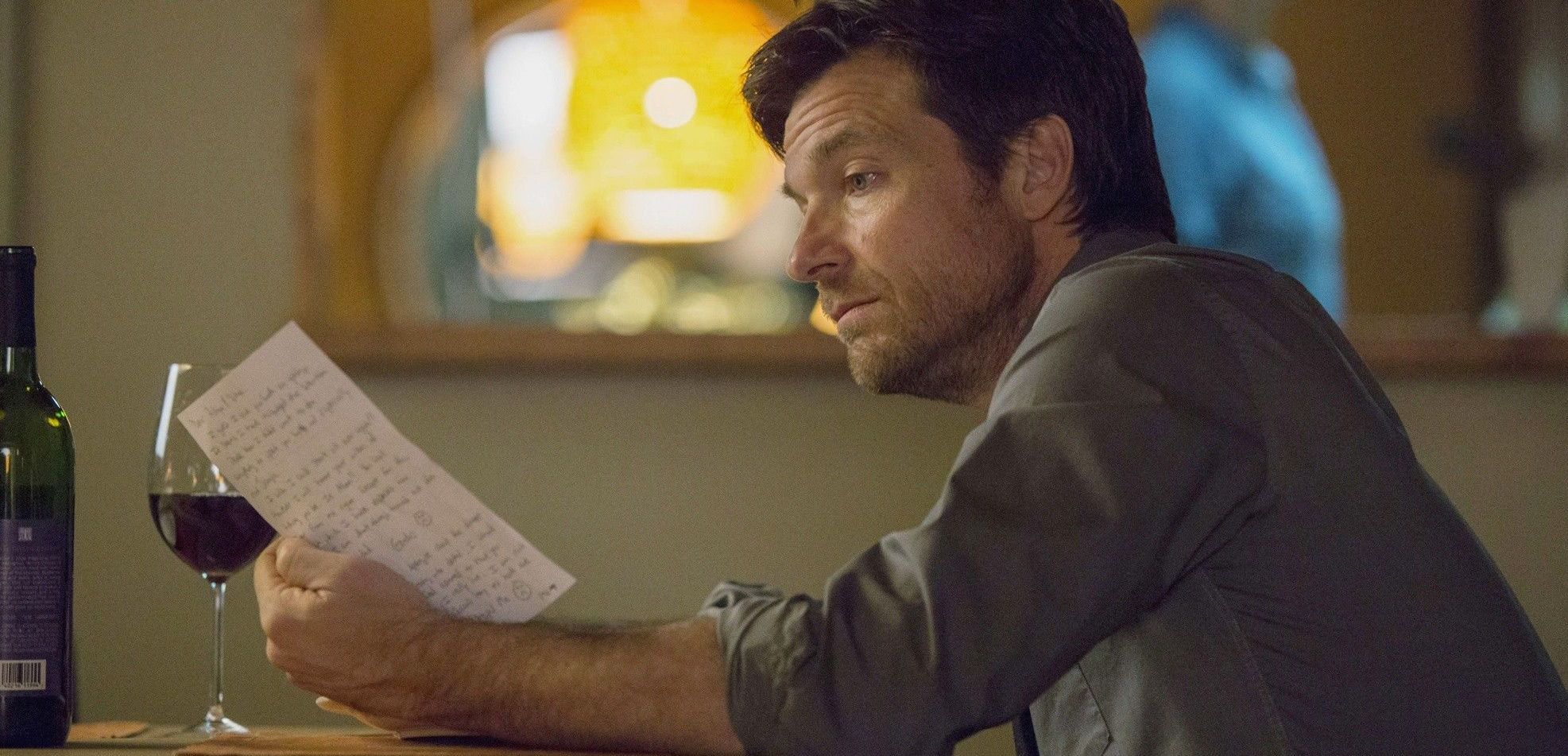

Of The Gift’s three distinct acts, the first is by far the best. As a short film, isolated and bifurcated from the remaining hour and change, it’s a startlingly well-observed analysis in social commentary that often left me twitching in my seat. The film is actor Joel Edgerton’s first time in the director’s chair, and he brilliantly uses the peculiarities around social awkwardness as a tool for razor-sharp suspense. At a cushy dinner party, Simon (Jason Bateman) and his wife Robyn (Rebecca Hall) enter an uncomfortable tangle of looks held too long, shifty-eyed silences, and an obvious vulnerability in how people speak when trying to conceal festering interpersonal tension. After relocating from Chicago to L.A. for Simon’s new job, Robyn lost her design firm, so when champaign hobnobbers inquire what she does for a living, Hall reacts with a slight shame in her face. In a similarly fine-tuned performance, Bateman plays Simon a few notches too loud, making his character a forceful, compensatory character who declares Robyn still does “so much.” With Robyn sidelined in the conversation circle and submissive, unable to speak for herself and Simon so over-cranked and quasi-macho, we see a stunning portrait of slickly specific details amounting to a devilish display of interpersonal awkwardness..

The first half hour or so deftly reminds of the Swedish Cannes winner Force Majeure (PSA: now streaming on Netflix), but it’s the rest that’s the problem. What was a measured dance of Edgerton’s ice cold and slow moving camera ominously observing slightly off human behavior stops being smart or cunning -- the two necessary ingredients of a slow-boil domestic thriller. The Gift’s nucleus is a so far unmentioned element named Gordo, “the weirdo’, the film’s best role that Edgerton cast himself to play along with his duties as writer and director. After running into Simon and Robyn seemingly by chance when they’re out homeshopping, Gordo reminds Simon they were old high school buddies and, surely, should catch up soon. Except that, while they went to the same high school, they weren’t friends and possibly even, as Edgerton’s script hints early on, were enemies. Carrying the social behavior motif on his shoulders, Gordo epitomizes what we’re meant to think of as the ultimate stalkerish weirdo.

He begins intrusively sending gifts to their new home. Of course, he overheard their address instead of being told it. Suddenly, he starts showing up. Next, he invites himself in. Multiple times. When Robyn’s home. Alone. Not even Edgerton’s nuanced performance as creep of the year can stop the film from being on the nose, although Gordo’s bound to remind you of at least one person you wish you didn’t know. The problem emerges when The Gift turns into a ridiculous game of cat and mouse that in real life circumstances would be easily resolved while also playing off every old-hat trick in the thriller book. Oh gosh: the dog’s missing. Did Gordo take the dog? Can we prove it? How could we?? It has the genre trappings of Secret Window or maybe a $5 airport novel, but none of the storytelling tact to make it as fun as that film, which is already a guilty pleasure. Almost every suspicion I had of what the next twist would be I guessed well in advance, but there’s pleasure in identifying which clues are red herrings and which climax in sadistic secrets and reveals later on.

Long sections of The Gift pass by without much happening and without the tight wired suspense of the first half hour. The stretch through the middle is a muddled drag, and even as things ramp up in the finale, the shock value is diminished not just by the lack of realism, but by a weird lack of plot or character development. What we get instead of a domestic drama/thriller is a breadcrumb trail of clues, each new morsel given out every 5 or 10 minutes, waiting for them to add up. This builds up to the ending that follows the same obvious pattern as many psychological thrillers before it, but to name which films it borrows from would be a spoiler. Some in my theater were gasping for breath and in a state of shock, but affected as I was (a medium amount), it wasn’t the guttural impact The Gift so desperately needed it to land a successful finish. Luckily The Gift is never boring, and the crisp tonal space of L.A. suburbia keeps things feeling unsettled but rarely in more than a minor key.

Edgerton’s a smart guy, and clearly designed his quirky debut with a defining theme in mind. Bateman, famous for his unlikeable everyman in Arrested Development, plays a character who is, in essence, in a state of arrested development. Early on he notes that some people change dramatically after high school while others stay exactly the same, clearly labeling Gordo the “weirdo” as identically strange as decades before. But it’s Simon and Robyn, and eventually you realize it’s every character in the film that’s locked in stasis, making this a movie ultimately ruminating on the possibilities of change. Secrets of past ‘versions’ of these characters come to a head in the ugly finale, arguing who you are is less about growing up and a lot more about social constraint. The bad guys are still bad, they’re just forced into good behavior to keep existing in society. A scary idea in a not-so-scary film.

C+

Follow Brendan Hodges at