Fascinatingly adapted about 20 years after Bram Stoker wrote the seminal novel Dracula by F.W. Murnau in 1922, Nosferatu is the original text that spun hysteria into popular culture for the next century. With Twilight, True Blood, Underworld, Anne Rice, and countless other examples, the genre shows no signs of slowing down. Murnau’s is the original vampire film, one of the first true horror movies ever made, and it’s nothing less than spellbinding. Unable to secure the rights to the novel, Dracula became Orlok, Vampire became Nosferatu, and the story has been changed. Nosferatu has reduced and reshaped the Dracula chronicle into pure cinematic art, and it’s the better for it.

It’s a silent film fixed with the interruptions of dialogue cards, and the discontinuous pacing of the early cinematic form has rarely completely won me over. Like many silent movies, sections of Nosferatu walk the delicate tightrope between slow and boring, but few films ever made, silent or not, reward the effort like this does. Nosferatu is one of those movies where its cumulative effect is far greater than any single shot, scene, or moment. Horror and dread slowly seep into you. And you don’t realize how much they’ve taken hold until it has almost ended, and by then it’s too late.

To the uninitiated, a well-intentioned real estate man named Thomas Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim) embarks to sign a new client, the elusive Count Orlok (an extraordinary Max Schreck in prosthetics best left discovered on your own), in his castle home in Transylvania. Hutter leaves his beautiful wife (Greta Schröder) with friends. Of course, Count Orlok bears sinister intent, and eventually a reign of terror falls in his roaming wake.

The original German title reads Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens, which translates to Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror. Axing the sub-head of the title makes sense for a cleaner, harder hitting name on a poster, but the original communicates something essential and true. Nosferatu is the 2001: A Space Odyssey of horror cinema, embedding a genre with the narrative, thematic, and visual ideas that will come to define it. It is a horror opera on the most epic of scales, with a minimalist story that’s more elemental than narrative. Henrik Galeen’s screenplay collaborates with the shadowy alcoves of folklore, with simple straightforward storytelling carrying an undercurrent of depth. No scene is wasted, with many suggesting a broader supernatural universe than the frame of Count Orlok’s tale. Patrons inside an inn warn Hutter of werewolves, and Murnau cuts to (what appears to be) a devilish hyena stalking a nighttime forest. What is the nature of this beast? The film does not say, but the hint is enough.

Like 2001 established for movies the issues of man versus machine, free will, God, and our place in the universe, all with an unblinking stare, Nosferatu unsuspectingly started as many traditions. Anyone who has watched a supernatural themed horror movie in the last 40 years will recognize tropes Nosferatu started or helped solidify. Horror movies often show a primary character finding a journal or (sometimes ancient) book that describes the otherworldly evil that will inevitably descend. The character, usually sharing a reality meant to be synonymous with our own, dismisses the writings as lunatic ravings. Often, they laugh. Equally as often, they later wish they didn’t. It’s amusing then, that a movie released in 1922 might have been the first film in the history of cinema to introduce this. At the same inn Hutter is warned of werewolves, he finds a book descriptively detailing all there is to know of vampires. We learn, for example, that vampires must carry with them, and live in, the tainted dirt of the Black Death. After reading, he gives out a full-bellied hearty laugh only to then literally throw the book onto the ground. What hogwash! What an odd thing this scene became a horror staple.

Each episode of Nosferatu distinguishes itself from the others in flavor and pace. Each is larger in scale, less forgiving, and more wicked. The call of adventure tricks Hutter into a mood of hopefulness and excitement, and Gustav von Wangenheim convincingly plays Hutter as a Tolkien-esque hero eager to see the world. The early sections of Nosferatu have the gleaming warm quality of the roadside travelogue film, which were little more than assembled shots of faraway lands and places, showing audiences exotic parts of the world they would never had the chance to visit themselves. The warmth quickly turns to the suffocating coldness of Count Orlok’s stone castle, a labyrinth of stretched narrow hallways drowned in darkness. Murnau’s mise en scène is visionary, and more subtle than Robert Wiene’s radical stylization in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Murnau’s effect is creepier and harder to dismiss: reality and nightmare are as one.

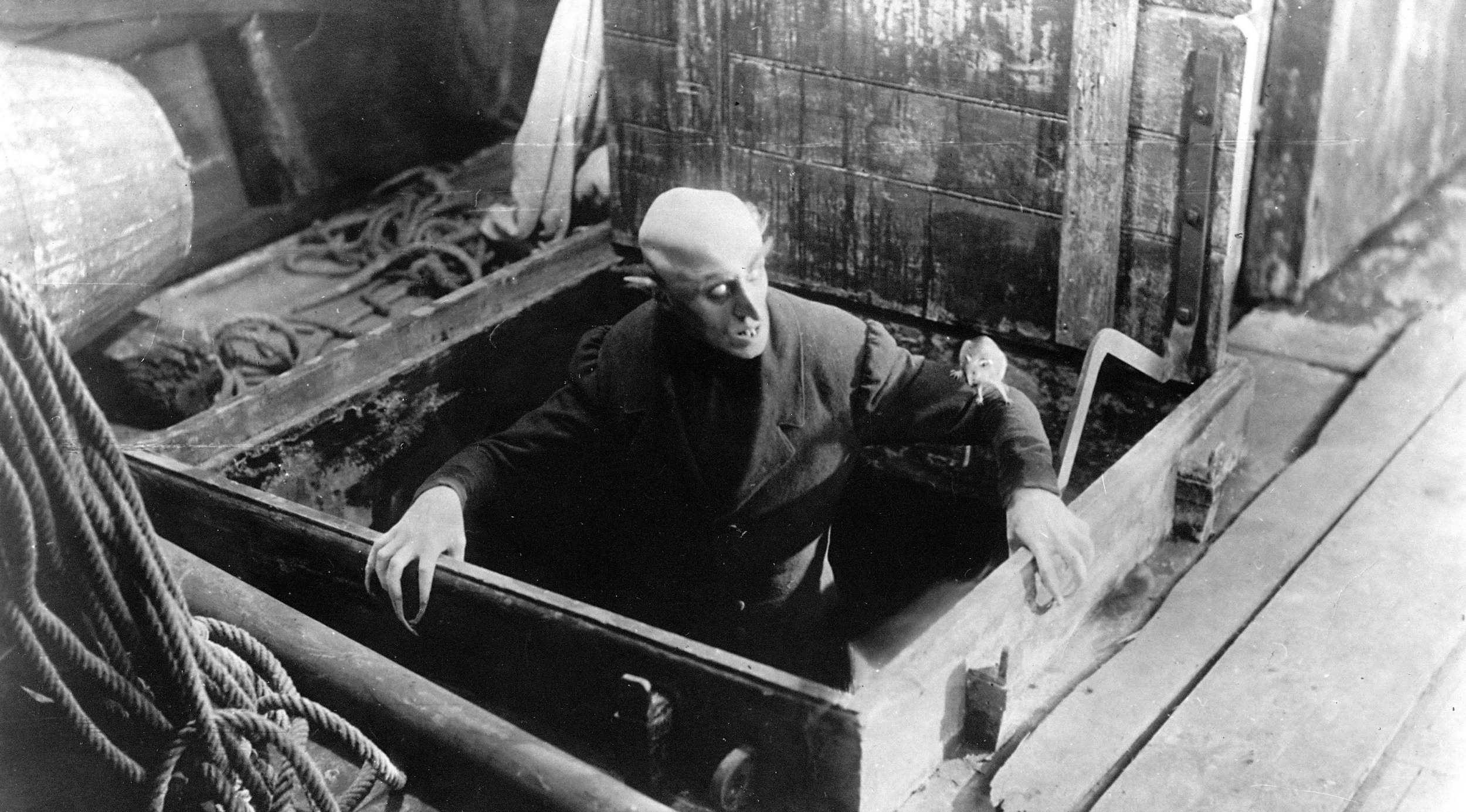

Nosferatu’s most memorable and talked about passage involves Count Orlok traveling on a ship towards the fictional German city of Wisborg. He travels in an ensemble of coffins, and the crew is unaware of their evil cargo. Never has there been a more haunting ghost ship. Here, Orlok becomes a phantasmic serial killer, appearing as a grim and deadly apparition, revealing himself as a translucent ghoul. In a cheap effect, the film was scanned in such a way that Max Shreck is invisible. Rare is it that the more dated a visual effect is the more effective, but that is the case for this sequence. Later, a ship deck door flies open and the rope around it uncoils. Neither were moved by a visible force. We can tell it’s fake, but the unrealism is just another thing that scarily clashes with a logical universe.

The images of the black transport ship starkly contrast the bright sea and sky, and shots where the camera is mounted to the ship falls and crashes into the waves have the indescribable feeling of panic. Point-of-view shots define Murnau’s style, and they’re used often. He traps us into the perspective of characters we wish we wouldn’t be, like when Hutter finds Count Orlok stalking his bedroom. We cut to Hutter’s POV, peering down a corridor to a centrally framed Orlok staring, eyes bulging out, hungry. But the ship is Murnau’s masterstroke of the motif, where our point of view doesn’t inhabit a person’s, but a ship’s, imbuing an inanimate object with the terrible fury of matter forced to life.

In the final stretch when the title creature arrives in Wisborg, the townspeople move like a mob of insects when caught under a vampire’s influence. The jagged motion of early cinema, the varying frame rates instead of the stable 24 frames per second that was standardized later, lends their motion an inhuman rhythm that gets under one’s skin. Unintentional, but Nosferatu proves art glorifies happy accidents. They chase and try to capture the villain and his helper put under the vampire’s spell. His spell, they don’t realize, has been cast beyond the shadow of one, and entrancing many.

The vampire’s abilities differ from those of Lestat, Bill Compton or Edward Cullen. Or almost any famous vampire. Instead of turning into a bat, commanding super strength, or any number of supernatural abilities popular culture tells us Count Orlok should have, his powers are more terrifying. It’s not just a fuming fear of death that gives the vampire its weapons of dread, but how Orlok threatens our sanity and our soul. His warfare is psychological, most startlingly shown by Ellen Hutter losing control of her mind and body. She leaves her bed and walks the balcony railing, putting her life in jeopardy. Ellen and the Count share a psychosexual connection, and he is many miles away playing the puppet master.

Murnau is fearless and treats his material without an ounce of camp (or at least outside what was normal for silent cinema, which begs actors for the louder style of theatrical performance). What should seem silly is hell personified on the cinema screen, and his reverence for mythology gives us no other option. We must treat the vampire, and so then the terror he brings, with seriousness. The vision on display is staggering. The stylings of German Expressionism, with its long contorted shadows and disfigured clashing shapes, has never found a more complimentary subject than the vampire. A terrifying, bone-shaking masterpiece.

A+

Please follow me on Facebook, Twitter, or RSS below: