Follow Brendan Hodges on

Ex Machina starts small, and where it easily could’ve gone the way of gatling guns and transforming robots with laser beam vision, it ends small too. It’s a brave move I like to think was motivated by art more than a small budget, a benefit of the doubt that by Ex Machina’s end writer and director Alex Garland has certainly earned. It’s a complex, haunting, and beautiful work that’s a spiritual sequel to 2013’s excellent Her, puzzling over the sooner-than-we-think discovery of the singularity. No, not the singularity at the heart of a black hole. The singularity, or “technological singularity”, is the moment in time when artificial intelligence, A.I., will surpass human intellect as well as control. It’s a sci-fi staple easy to think has been expired of fresh possibilities. Ex Machina is a 108-minute argument that proves that idea wrong. Some have cried out against some goofy plot problems, but this is exactly the sort of work where that’s what matters least. More an opera of ideas than a production of action, violence, or deafeningly loud melodrama, questions are asked but rarely answered. Ex Machina is the first great film of 2015.

Domhnall Gleeson plays Caleb, an up-and-coming computer programmer who works at a company stand-in for Google called BlueBook. In a gorgeously filmed sequence absent of almost any dialogue, Caleb wins an elite VIP trip to visit the eccentric and reclusive genius CEO that invented BlueBook at age 13. His eccentricities extend to a bald head and burly man beard, and he continues with all the social ease of a pitbull around a collie. His name is Nathan (Oscar Isaac), and he’s working on something new that’s more top secret than top secret. He forces Caleb to sign an NDA that gives up any right to privacy for at least a year. Every conversation he has, online or in person, will be monitored. Tipping Caleb to Nathan’s work, he’s asked if he knows what a Turing Test is. He says yes. It’s a test designed to see if someone can talk to a computer without realizing it’s an artificial intelligence and not a person. For the first time in human history, an A.I. may have been created and her name, appropriately, is Ava (Alicia Vikander). She’s beautiful, resourceful, and capable of conversation so advanced she can make jokes. She flirts and tempts you to flirt back. It’s Caleb’s job to determine whether she’s a real, genuine artificial intelligence or something less revolutionary.

What unfurls is a fascinating reflection on artificial intelligence that doubles as a captivating character study, one expertly performed by Isaac, Gleeson, and Vikander. A common mistake is reducing characters to just one thing; i.e., Billy is a walking symbol supporting the war and Sally is the mouthpiece for pacifism. The conversations between Caleb, Nathan, and Ava are multi-faceted and nuanced, agilely blending philosophy and art into dialogue scenes that often take place over beer or vodka. Like casually talking about how A.I. will eclipse and eventually eliminate humanity. The robots of the future will look back on us the way we think of the first men. You realize they’re probably right, but in the way you nod your head when a coworker has a surprising insight in off-the-cuff conversation rather than from a TED Talk. Garland’s screenplay wields the athleticism of an olympic gymnast, having the balanced footing to make conceptual movements that are neither big or small; they’re just right.

Films as elegant and cohesive as Ex Machina are fun but difficult to review at first glance. They withstand the obvious ins of analysis, where plot, character, and theme slip into each other, like chemicals bonding into a unified element. The properties can be difficult to trace. Like a delicious meal with finely balanced spices, Ex Machina boasts an uncommonly sophisticated handling of its ingredients, delivering a plate of old-hat themes reinvented by their distinct mixture. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is recalled in cutaway shots to gorgeous mountain hills and pastures, sometimes covered in a thick fog, using gothic imagery to warn of the possible perversion of nature. Man craves becoming a god and in Ex Machina he may have; life may have been created. The nature shots act as a foil to cold steel surfaces. The same foil found between man and machine by Caleb and Ava. The natural world is at war with the unnatural, and Garland skillfully questions the actual differences between the two. Nathan proposes to Caleb whether humans are any less programmed than A.I., only by nature instead of by man.Caleb is uncomfortable with the notion. Like Neo in The Matrix, it’s normal to want to feel in control of your own life.

A Jackson Pollock painting doubles as an explanation for the distinctly human acts of impulse and impression, characteristics essential to discover in Ava to determine if she is, in fact, a genuine artificial intelligence. Nathan imposes that Caleb and him need to act like just a couple of dudes, and their contrived interactions (as well as spoilery content late in the film) possess Ex Machina with a haunting commentary on modern relationships. Especially modern relationships as a result of the internet. They’re inward and forced, selfishly assigning what you want onto the other person and expecting with entitlement your needs will be met. Humans acting like robots and robots acting like humans has been a theme in science fiction film since 2001: A Space Odyssey, but connecting questions of artificial intelligence to the digitization of social interaction is almost poetic in its execution. An unease hangs over the coldness of Nathan and Caleb, people whose feelings are seemingly as abstracted as Pollock’s expressionistic drip painting.

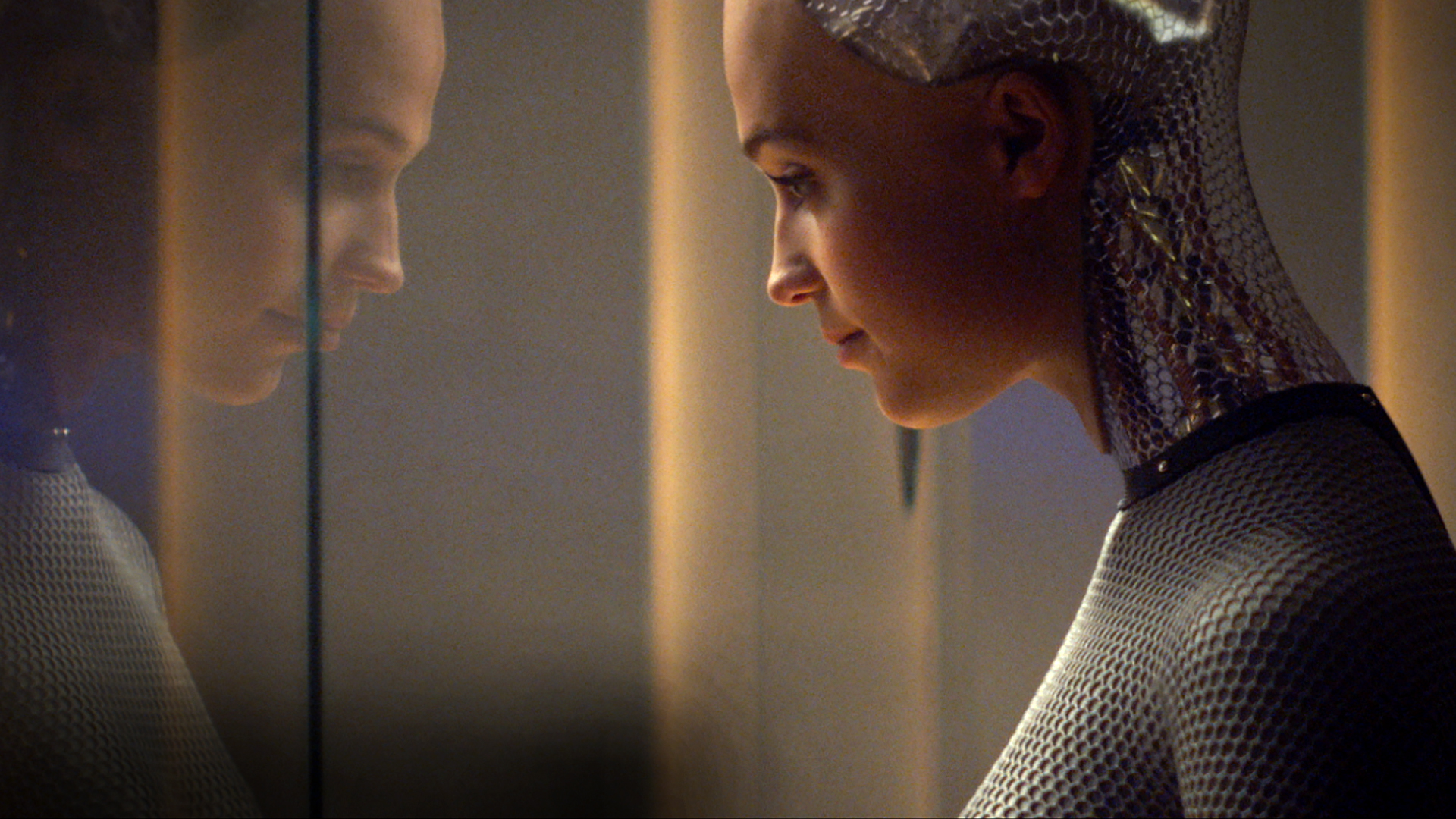

It’s inevitable at least one “human” character will be revealed as having been a robot all along; it was an assumption I had entering the theater. But that it could be believably any of them might be the most alerting thing Ex Machina has to offer. Robots and humans can’t coexist forever, and the dividing line grows thin. Seeing the two—the human and the machine—mutually represented in Ava’s design is instantly iconic. Her sensually designed frame has smooth curves and nicely shaped metallic breasts, and with what seems like a soft skin covering only her hands, feet, and face (but not the rest of her head). She’s a believably confusing thing (should I have said person?) to be around. I didn’t know what I thought or felt about her until suddenly I stopped questioning it. She made me laugh and she made me smile, and eventually I felt for her equally as I did for the human characters. I fell for Ava. You will too.

B+

Please follow Brendan Hodges on Facebook, Twitter, and RSS below: