In honor of the recently released Gone Girl, I’m reviewing each film in David Fincher’s staggering career.

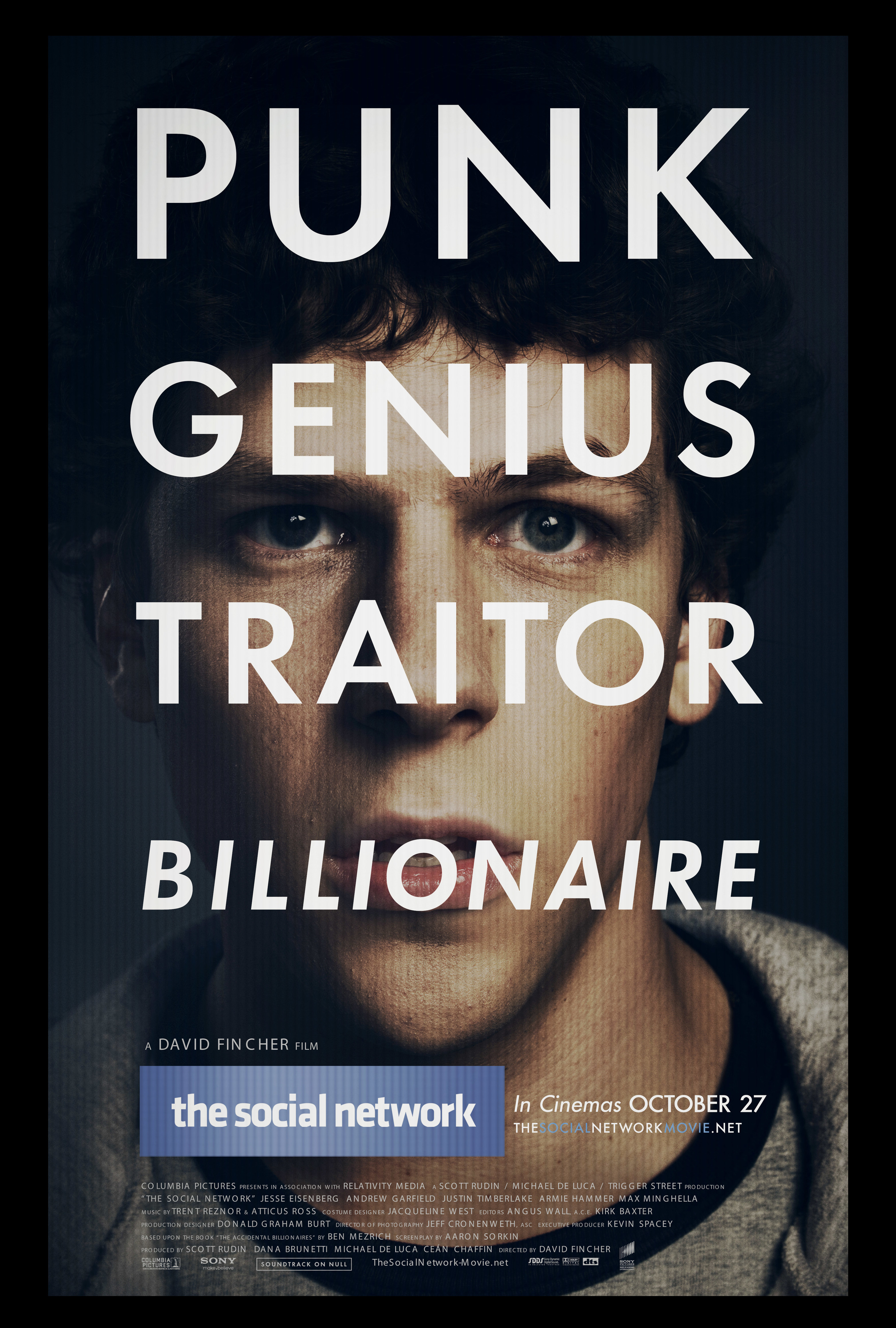

At what point do you know you’re watching a masterpiece? Did it hit the 1941 movie-going audience while watching Citizen Kane that it was one of the greatest movies ever or after? Was it on the first viewing, the second, or maybe the tenth for the tastemakers to whisper “masterpiece”? Famously, it took Citizen Kane a while to be deified as the greatest film of all time, growing in the collective consciousness of, well, just about everyone who saw it. However, some films are so epic in their scope and thematic volume that their greatness is instantly registered, like Lawrence of Arabia or Chinatown, both of which won rave reviews and plentiful Oscar attention. All three of these films consistently rank highly on best ever lists, and in fall 2010 they greeted a new member: David Fincher’s masterful The Social Network. It had the swift embrace of Lawrence and Chinatown but the thematic underpinnings of Kane, and both the film and Fincher ought to have won Oscars in 2011. It broke into theaters with something to say so vital and so inspired, like the social media website from which the film has its name, it’s amazing it took that long.

The Social Network is Citizen Kane for the contemporary era, using the margins of big business, greed, and betrayal as the touchstones of loneliness and isolation. It is the story of Facebook’s founding and of the he-said, she-said murkiness over who should get credit for the most important innovation since the Internet. When we first meet the famed Mark Zuckerberg (Jessie Eisenberg), he’s a snobby sophomore at Harvard University, and for reasons foggy to him but crystal clear to us, he’s pissed off his cute girlfriend (Rooney Mara). She breaks up with him, leaving him reeling with something to prove. Drunk and feeling seditious, he creates facemash.com, an Internet application where you rank girls by picking between two pictures. Amazingly, the site netted 22,000 hits and crashed the Harvard network. Enter the Winklevoss twins (Armie Hammer, Josh Pence) and Divya Narendra (Max Minghella), who invite Mark to work on “Harvard Connection,” a social networking site that promises its members exclusivity. He agrees. Not much later, he tells best friend Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield) about his idea for a website that will transport the entire social experience of college. This is what became facebook.com, and it sets forth a hailstorm of legal disputes that raise issues of ownership, creativity, capitalism, and loyalty.

The genius of Aaron Sorkin’s thousand-word-a-minute script and Fincher’s never-better direction is how it makes a movie about kids typing at computers play like a thriller. It’s Fincher’s most relentlessly paced film, taking the brilliantly structured script and tightening to the point of near asphyxiation. The longest number of seconds between dialogue could probably be counted on one hand, and tense is The Social Network’s natural state. There are few opportunities for us, or the characters, to breathe. Not a single scene is wasted, and the film constantly propels forward with unyielding momentum. When we enter most scenes, it’s as though they’ve already started, giving The Social Network a feeling of perpetual in medias res, a sensation enhanced by the flowing quality in between scenes. Jeff Cronenweth’s moody cinematography paints Johns Hopkins University (the film’s stand in for Harvard) like a beautifully lit crime scene, an orgy of shadow that’s a potent metaphor for the hollow darkness in the hearts of the characters. The constrictive depth of field makes characters seem like they’re suffocating in their own environments and makes us claustrophobic, and Fincher giving The Social Network the same visual cues as his serial killer films was genius.

To make facemash.com, Mark had a series of computer moves well beyond the comprehension of 95% of the audience. First, he has to hack different databases from the Harvard network, then code the site, and then use an algorithm Eduardo supplies for it. Mark’s concurrent blog posts are narrated to us by Eisenberg, who was born for Aaron Sorkin’s indulgent but beautiful dialogue, and his charisma helps make the sequence lucid. Sorkin finds the perfect heading to lead us through the techno babble of the World Wide Web, and the trick is in how he underscores these moments with clearly defined motivations. Not knowing what “Emax” is doesn’t matter. It’s one thing that Sorkin and Eisenberg gave the scene clarity, but it’s Fincher that made it feel like a set piece. The rhythmic editing (that won an Oscar) cuts between angles in the same frenetic style as the Bourne Trilogy, giving the scene the same visual vocabulary and feel as an explosive action sequence. It’s not the only one, and Trent Reznor’s and Atticus Ross’ pulsing score that’s both the sounds of creativity and of cynicism drives it.

Last year, there was a lot of talk, including some by me, that Gravity was the apex of digital moviemaking. Pre-production was its postproduction, and filming looked like something out of a 1950s matinee science fiction, with a ‘light box’ constructed of LED panels and a harness for the actors to assemble their space spectacle. It occurred to me David Fincher’s best movie, The Social Network, is a perfect product of the digital era as well, destined to be looked back upon for many reasons, not the least of which is for its innovation in cinema style. The flexibility of the digital camera allowed him so many setups a day he could dance between multiple angles with unflinching confidence, and the style he started with Zodiac is perfected here. The pleasing dreariness of Cronenweth’s cinematography was only possible with the advent of digital cameras, using the lamps on the set as primary light sources. Only a digital camera has enough latitude to maintain clarity in dimly lit environments, and the results speak for themselves. Fincher’s aesthetic is a stunning example of digital cinema, one to be borrowed from in the years to come.

The Social Network is a cutting indictment on modern life. Mark Zuckerberg is not an asshole; he’s socially awkward. There’s a possibility of Asperger’s that’s shown in Eisenberg’s detailed performance, and he’s as clueless to social decorum as I am to hacking Harvard’s network. His behavior is logical and to the point, and while his comments seem undercutting and coated with passive-aggressiveness and might make him seem ruthless, he’s just cut off. As Fincher notes in the excellent commentary track, when Mark ignorantly asked, “Doesn’t anybody have a sense of humor?” to the Harvard administrative board when they didn’t find Facemash funny, he means it. He’s the ideal hero for a global society increasingly in a state of disconnect. Mark has the creative spark of a thousand suns. His inventions are revolutionary, applying perceptive observations to a website perfectly primed to explode to 500 million users.

But success, as it has been defined today, increasingly hurts the soul. It is ruthless and competitive, but, worst of all, it is entitled. We are entitled. Every major player in The Social Network is a victim of commodified thinking; each of them is right and each of them is wrong. The twins and Narendra are casualties of a game they’re used to having rigged to prime their own success. He didn’t steal their idea. He had a better one. His chair analogy is apt, and he didn’t do anything corporate raiders and capitalist entrepreneurs don’t do every day. It’s easy to see the point of view of both sides, but Mark’s innate prickliness makes him seem so much guiltier than he actually is.

SPOILERS: A popular argument for Mark’s narcissism is cutting Eduardo out of the company. However, from Mark’s point of view, he did little wrong. Or, rather, he did little more wrong than Eduardo. Mark’s best friend refused to take good advice and instead got lost in his own self-worth, thinking he could do a better job in New York City than Mark and Sean Parker (the founder of Napster and played very well by Justin Timberlake) could do in California. He was wrong, and when that was pointed out to him, he threw a temper tantrum that almost crashed Facebook forever. As Parker says, “That’s life in the NFL.” Eduardo was right to feel threatened and betrayed, but so was Mark. They each traded friendship for ego. END SPOILERS

In the tech-driven city of Tokyo, Japan is experiencing an epidemic where citizens not only stopped having kids, they stopped having sex. Phenomena like that points to the ever-increasing relevancy of Fincher’s masterwork, making The Social Network the ultimate parable generations in the future will look back on as a cautionary tale and ask, “Why didn’t we learn?” A masterpiece.

A+

Other Fincher Reviews:

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

Please follow me on Facebook, Twitter, or RSS below:

RSS FEED