Cinephiles talk about long takes the way 20 year olds talk about magnums in the condom aisle: something a gifted few try to get, and fewer still can use. The phallic obsession, as jokingly noted in sitcoms, romantic comedies, and, slightly more credibly, healthcare professionals, doesn’t make sense. After all, size doesn’t matter—it’s how you use it. This is an apt metaphor because the key to uninterrupted shots lies entirely in their application and not merely in their presence. It’s about context. Martin Scorsese’s classic Goodfellas features one of the most famous tracking shots in the history of movies, but it amazes not only because of the aesthetic oomph of the shot itself, but because it’s perfectly placed in the movie. If movies are about pacing and if pacing is about rhythm, then a long take has an uncanny ability to disrupt, intrude on, and distract from the film overall.

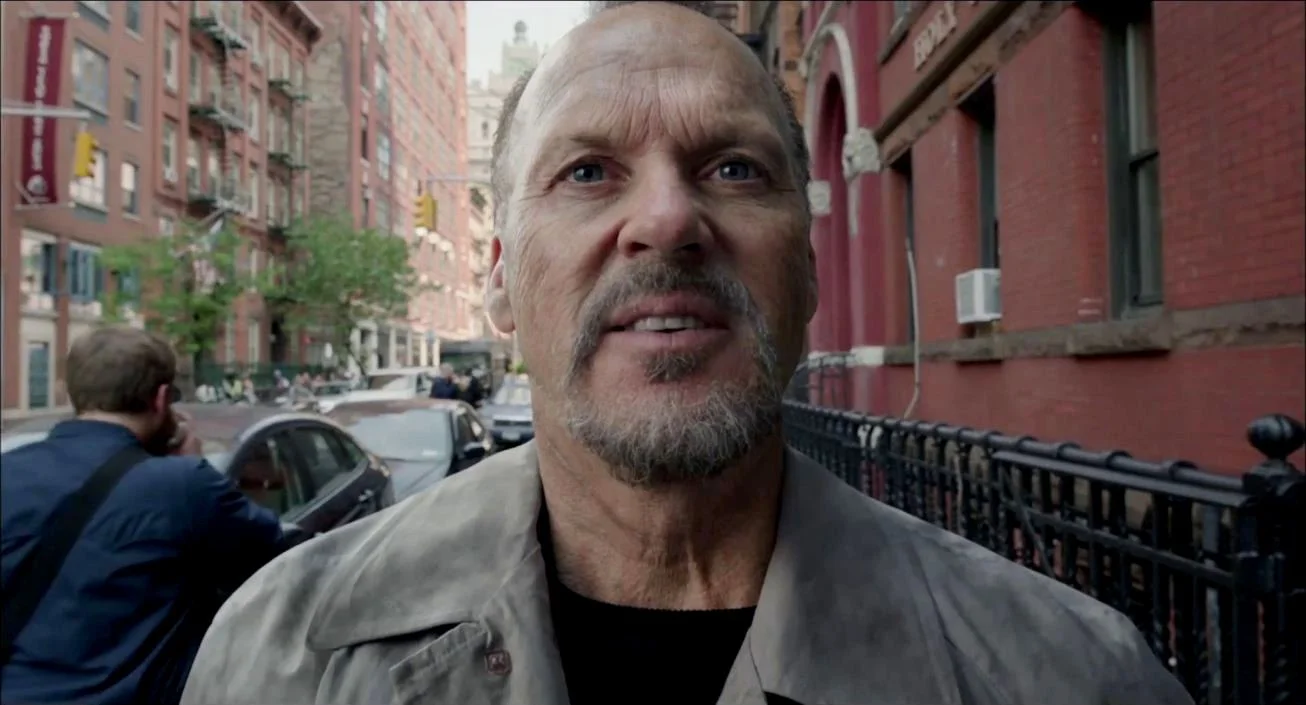

Babel and Biutiful filmmaker Alejandro González Iñárritu is out with a new feature, Birdman, and it, along with a select few films in the history of movies and moviemaking, appears to be one sprawling, epic uninterrupted take for the duration of the entire film. It’s a wildly, mind-numbingly complex undertaking that automatically launches Birdman into the pantheon of the most ambitious films ever, something that’s refreshing to say without an ounce of hyperbole. The same can’t be said for Riggan Thompson’s (Michael Keaton) stage adaptation of Raymond Carver’s short story What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, which is resolutely not the most ambitious play in the history of theatre. Riggan is an aging star, a former superhero icon that is a Batman stand in named Birdman. His history and on-screen persona, like all of the chief characters in the film, meta-resemble the real life history of the actors portraying them. Riggan stopped playing Birdman in 1992, refusing to continue the franchise. Keatan said no to Batman Forever in the same year. To make himself credible him as “serious” Artist (capital A!), he’s producing, writing, directing, and starring in his adaptation. The huge and amazing cast is almost as much of a special effect as the single take, including Edward Norton as a dickish perfectionist actor in an award worthy performance.

On the most superficial and surface level, Birdman is a simple behind the scenes story about bringing a play to life. That is, until you realize the camera isn’t going to cut, that we meet Riggan Thompson (literally) levitating in his dressing room in his tighty whities, that the film might be magic realism or might be about a schizophrenic, that Riggan talks to himself in a BaleBat voice, that the whole film is a running parody, satire, and black comedy of media, celebrity, art, and achievement, and that the whole film is a celebration, not an indictment, of cinematic art. It’s as though Iñárritu is screaming from the rooftops this is what cinema can do, which, depending on how much you like the movie, might sound like a self-confident artist in his prime, or an obnoxiously self-important filmmaker with a head that needs to get shrunk. Moments of Birdman feel like a revolution, a breakthrough in film art, but so many others were abrasive and discordant. These are the same properties of Jean-Luc Godard, the French New Wave auteur whose films, particularly the masterpiece Pierrot Le Fou, have such presence in Birdman. But, unlike Godard, Iñárritu’s no genius.

But none of the film’s other successes or failures—and it has plenty in both categories—warrant as much attention as the truly astounding aesthetic achievement of Iñárritu and his extraordinary director of photography Emmanuel Lubezki. The question is, however, if the buzz around the picture (93% on Rotten Tomatoes) is attributed to the voodoo of the long take—the hype, the praise— that minimizes critics and film fans to 20 year olds gawking at massive long-take condoms previously purchased by cinematically well-endowed movie giants like Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kubrick. The answer is maddeningly complex: the style is at once what makes Birdman the marvel that it is, but holds it back from being the amazing film it isn’t.

Unlike The Grand Budapest Hotel, which had a clear, focused camera following highly choreographed action, Birdman’s camera is frenetic and frenzied, but trying to do the same thing. Scenes fluidly fall into place before (deliberately) breaking apart. The effect is one of extraordinary realism, with the camera stampeding through hallways and zipping around corners, with the cast always on cue, each shot immaculately staged in advance. It feels as rehearsed as theater but as improvised as jazz—no coincidence given the film’s ringing, percussive jazzy score–imbuing in the film alternating states of harmony and disharmony. As an annoying result, some key scenes that should have dramatic heft are as weightless as the characters in Gravity, collateral damage for a rhythm that’s so stop-start. Confessions of grief and loss become suffocated by the maximalism of Lubezki’s camera, and it is here where the performances work wonders: they’re Birdman’s first aid kit.

Keaton and Norton are the heart and soul of the film, and if at any point Birdman loses you, and it almost lost me, their electrifying performances pull you back in. They are amazing, giving highly nuanced and considered performances that catapult them into the awards race. More than anything, they animate dead characters back to life. The rest of the cast, including Naomi Watts, Zack Galifianakis, Andrea Riseborough, Amy Ryan, and Emma Stone, do what is required. The long takes orient the viewer so closely with the perspective of each character we follow that it’s like an emotional close-up, and it has the unintended effect of zooming so far it’s like we can’t make anything out. Birdman can be cold, and in a movie that wags its muchness in your face like an excited toddler with a new toy, it becomes tedious. The performers are the heart, not the filmmaking.

Birdman’s been called a marked departure from the fatiguing pessimism of the rest of Iñárritu’s work, but his latest might actually be the most cynical. It loves cinema, but hates people. The only optimism is that it suggests once we find what we’re looking for—whatever that may be—we get our curtain call, and can leave the stage for good. Its sardonic tone tries to take on the subtlety of a silent assassin, strategically and invisibly knocking down targets—a problematic ambition to begin with— but in reality it’s as muted as a guy dual wielding rocket launchers. There is collateral damage, and no trope is unscathed. In Birdman everything is made into a punch line. There’s the method actor so devoted to his art he’s only real on stage but fake everywhere else, the late-comer rising star, the star crossed lesbian experimentation, the culture of drug abuse in show business, the stupid empty power of viral fame, the washed up star trying to gain meaning, and the sour, power-hungry critic.

There are two scenes in Birdman that lay deep into critics, harshly calling them failed artists so they write reviews to bitterly compensate. Critics have responded in kind, calling those moments overblown, misjudged, or plain offensive. If Iñárritu and the other screenwriters (Nicolás Giacobone, Alexander Dinelaris, Jr., Armando Bo) have a proxy, it starts with the self-doubt of Riggan’s subconscious, but, ironically, it ends with the critic. Birdman is angry at everything, criticizing, satirizing, and insulting anything it can think of, possibly including itself. It’s self-reflexive to a fault, so concerned with its own self-conscious status as a work of art it ends up becoming a victim of its own contemptuous purpose. Underneath the spellbinding aesthetics and can’t-keep-your-eyes-off-them performances, Birdman suffers from creative defeat. Little is said that’s new or particularly interesting (we’re haunted by our past? no!), relying on the actor bandaids and one-take CPR to keep the film alive. It fails to do much more than point and laugh at heartbreak and tragedy, ultimately suggesting the only antidote for reality is escape, not catharsis. That’s not depth, that’s adolescence. Luckily, thanks to its ambition and artistry, Birdman still soars, even if it dips and drops like a weaker bird.

B

Please follow me on Facebook, Twitter, or RSS below: