Smaug is amongst the finest things Peter Jackson’s ever brought to the screen, and the dragon earns an extra lap around the bases. Pure. Movie. Magic.

Read More

You're Custom Text Here

Smaug is amongst the finest things Peter Jackson’s ever brought to the screen, and the dragon earns an extra lap around the bases. Pure. Movie. Magic.

Read More

It’s the best film he’s made yet.

Read More

As it turns out, while Lee’s Oldboy undeniably fails as a remake, as a pulpy genre piece, it works.

Read More

But, if it's Francis Lawrence who pushes down on the gas pedal to keep the film rolling, it's Jennifer Lawrence who slams it to the floor.

Read More

It’s a kooky off-kilter delight.

Read More

The actors sell these moments so well, they earn the cliche of wanting to walk up to the cinema screen and warmly hug the characters for support.

Read More

It gets boring, and it becomes a temptation to secretly pray characters erupt into song and dance with Thor star Tom Hiddleston taking center stage, falling to his knees, and singing “I dreamed a dream in time gone by.” Luckily, The Dark World is, if nothing else, extremely confident in its grand ambitions. It’s also extremely fun.

Read More

The Counselor, Sir Ridley Scott’s latest blow in a series of vexing disappointments (Robin Hood, Prometheus), is a confounding and pretentious snafu that’s puzzled at what it wants to be. Pulitzer Prize winning author Cormac McCarthy (Blood Meridian, The Road) wrote the screenplay, his first screenplay, and is responsible for the film’s worst failures, and not even the amazing cast of Michael Fassbender, Penelope Cruz, Javier Bardem, Brad Pitt, and Cameron Diaz can totally rescue it. The confusion begins with its tone, and its closest cousin in genre is certainly the neo-noir, but only on a cosmetic level that influences the broadest possible structure of the plot. Tropes of the Western hero are also in play, written to conjure a grandiose stage of scope and scale for the characters to occupy. This is usual McCarthy territory, literally and figuratively, including 2007’s best picture winning adaptation of No Country for Old Men, which is a much different beast than this picture and defies comparison. Unlike previous work by McCarthy, mastering and/or subverting these conventions is not a priority, and that’s where the problems begin.

Take a look at our nameless protagonist, referred to only as Counselor. This staple of the Western is normally used to construct a hero of mythic dimension, but here Michael Fassbender’s “Counselor” couldn’t be further from Clint Eastwood’s Blondie. Instead, Counselor coasts through his vanilla lifestyle passively, spending most of his screen time letting himself get told what to do by the characters around him. Brad Pitt’s infinitely charming Westray, a scholar of the drug trade, is acutely aware of Counselor’s lack of confidence, even pointing it out to him in as a plea to back off from making a terrible mistake. We realize his chronic state of insecurity is meant to make a statement on the modern decay of man and greed, so all that remains is your business title. Thus, his profession becomes who he is, and why he’s never named beyond his job. If the viewer’s meant to relate to this, it doesn’t work. He’s unlikeable, and worse, bland. His confusion is meant to be one with our own, but he becomes that frustrating friend always asking for advice but never taking it. Thank the movie gods for Michael Fassbender, or the chief character wouldn’t have worked, aided in part by great chemistry with Cruz.

A dramatically stationary main character damages the film, but the pacing cripples it. Wisely, McCarthy never leaves the main characters off screen for more than a few minutes, storing the brutally violent bits lingering in the shadows, and erupting only occasionally with the most shocking murders on screen this year. Bardem’s character Reiner as well as Westray both tell cruel anecdotes on what these cartel thugs are capable of, but by showing such restraint in when and how we see them, they are never personalized or given a sense of soul. This evokes the feeling of a sub-human industrial complex of misery and suffering, making death in the desert a frightening certainty. This intends to shake up the stakes and and provide rocket fuel for the film’s motor, and indeed it would have, but the driver never really hits the gas. The pacing of The Counselor mimics the experience of driving a Lamborghini Mucielago, a 632 horsepower beautiful beast of a car, through a 20 mile an hour speed trap. In this metaphor, the speed trap is the dialogue.

Like McCarthy sometimes writes female characters as suffering from penis envy, he wrote The Counselor with book-envy. So much of the film’s imperfections rest on the armchair philosophy characters choke out at eachother, like they’re coughing up hairballs of nonsense they hope made more sense than they thought. This works in literature, but it can’t in film, not when it’s this incessant. Bardem’s by far the most proficient at this, followed by Pitt, and they gave their lines meaning I’m not convinced they’d have had otherwise. Diaz isn’t so lucky, and hardly ever sounds convincing. Her performance is like a magnet, at times you can’t but be helped to give into her seductions, but in others you’re compulsively forced away. To the dismay of cinemagoers expecting a thriller, they’ll find a string of set pieces meditating on greed, greed, greed. Nearly every character is a tragic hero in some way, whose fatal flaw compels them to be greedy even when knowing they shouldn’t. Breaking the rules is a noble task, but breaking so many of them so as to alienate your target audience is not. Were McCarthy and Scott less prolific figures, they’d have heard more “NO!”’s in pre-production and found a finer gradation between dialogue right out of a Terrance Malick film voice-over and pulpy fun. There’s still enough of the latter (including the most enjoyably strange sex scene this year) to make the film somewhat enjoyable, and the cast, direction, and totally the unique experience alone is of high value, and boosts the film’s overall score.

Repeat viewings may unearth the hidden meanings beneath the inaccessible screenplay, but as it stands today, The Counselor is a pretentious and indulgent movie that wished it was lyrical literature but instead came out a lackluster film. Even while being modestly enjoyable, it is one of the biggest disappointments this year

D+

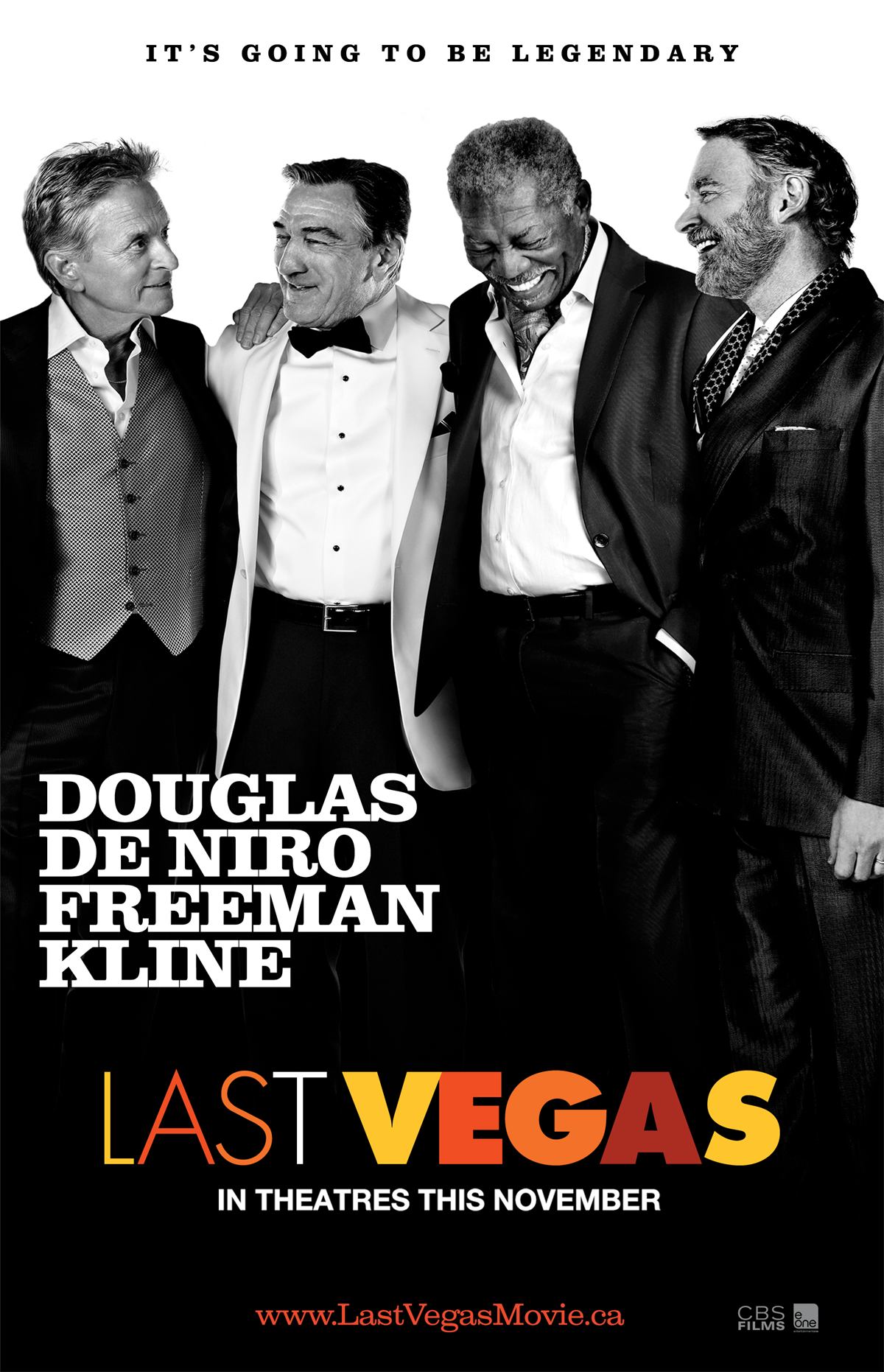

Film studios hope to release as many films as possible to cover as wide a breadth of demographics as they can, and have developed sophisticated tools to make and market the films as appropriate. The biggest moneymaker is the tentpole action film, which asks to bring in the high school and college crowd, usually men, but more recently studios have worked to call in the fairer sex. A smaller but still highly profitable niche market is what I call the “old fart fish out of water” comedy, enlisting relic A-listers to look confused, laugh about the good ‘ol days, and learn a warm lesson about old age before hitting the grave. You could question the profitability, especially since they’re usually universally panned by critics, until you take a gander at the receipts of these films, like 2007‘s Wild Hogs that made a whopping $253,625,427 at the global box office. So, it’s easy to understand using Morgan Freeman, Michael Douglas, and Robert DeNiro front and center in this year’s blockbuster of its genre, Last Vegas. It was a smart move, not because the film’s any good (it isn’t), but because the natural charisma of these film legends, along with the lesser known actor Kevin Kline, might just make Last Vegas worth watching.

The spunk and enthusiasm coursing through National Treasure, the most famous film by director Jon Turteltaub, is totally absent here, and instead feels like a leaderless whipping on the patience of audiences. It’s a rare film that tempts me to check my smartphone for the time, much less one where I’m itching to after the first twenty minutes. It’s the sort of studio slosh given to filmmakers as a punishment, and since Tureltuab crashed The Sorcerer’s Apprentice into the red and unable to recoup its budget, I suspect that was the case here. With that in mind, the palpable disinterest on the part of the filmmakers makes sense, robbing the film of the energy it ought to have. Unfortunately, since the film’s primary setting is a city internationally known for its shimmering buzz, this problem escalates. Furthermore, the screenplay is overflowing with cliches to such a heavy extent the cast barely treads water strong enough to inject personality into an otherwise directionless script and film. Tureltuab seems all too aware of these shortcomings and tries masking them with a zillion sloppy “haha” montages. It doesn’t work.

Though, if there’s one thing deserving of praise within the pages of an otherwise insipid script, it’s that there are genuine surprises with the directions it takes as the film continues. Sure, most are predictable, and the surprises still aren’t revelatory, but at least screenwriter Dan Fogelman bothered to include more than one. The cast is largely great, and add enough moxie and charm to forgive some of the unsavory elements of the film. Each of the three big stars take a fun jab at their current on-screen personas, although Freeman’s coasting every bit as much as in Oblivion earlier this year. Douglas and DeNiro are the heart of the film, adding layers to characters that dare to stir some emotion in late-act dramatics. It’s no surprise they share tangible chemistry together, but Mary Steenburgen is an eye-opener from the moment she graces the screen, and still Hollywood beautiful at 63 years old.

If only the rest of the film were as lovely.

D+

How much you find yourself enjoying The Fifth Estate depends on several factors outside the usual criteria of film criticism. For one, the film makes no secret (sorry) out of a general support for transparency, at least in some regulated form, but poises itself to smear Wikileaks founder Julian Assange almost as much as the mainstream American Media. By the final stretch of the runtime, any remaining supporters of Assange are shown as foolish and even naive. The filmmakers hope this arc mirrors those sitting in the cinema, but unlike better films that work to humanize each opposing character, such as David Fincher’s contemporary masterpiece The Social Network that this film borrows from heavily, it becomes uncomfortable how melodramatically the filmmakers hope to convince viewers to join their side. In fact, such a heavy handed approach won’t just alienate a huge portion of its audience, but risks exciting sympathy in those that loathe and resent Assange and his actions. That’s a major problem for a film anchored by heated disputes between parties, and in addition to failing to present the material in a complex and stimulating way, it also guts the drama of any potency.

The second factor for enjoying the film, however, rests on an item soon to be mega star Benedict Cumberbatch has openly found deeply troubling: fanboying for him. That’s not to say Cumberbatch’s performance requires some level of fan bias to enjoy, to the contrary, he’s freakishly dead-on as Julian Assange. If the performance seems understated and veering towards unemotive, it’s only because Assange himself wields those traits, and it’s the subtitles in Cumberbatch’s construction that completely sells him as the white haired revolutionary of media and transparency. It isn’t a transformative performance but it has no reason to be, and unlike other actors hoping to rise the Hollywood ranks with showy moments of ‘loud’ acting, he (mostly) plays it straight and cool. Although Assange has publicly denounced the film at every given opportunity and a letter protesting Cumberbatch’s invitation to meet him has gone viral, if he ever submits himself to watching the film, Cumberbatch’s portrayal might be the one thing he enjoys at all. The remaining cast are merely functional, which is a bitter disappointment from so many highly capable performers, such as Daniel Bruhl who recently had a fine turn in Rush, as well as David Thewlis, Stanley Tucci, and Laura Linney.

The reason, then, that fanboying plays a such a crucial role enjoying The Fifth Estate is because outside of the many compliments justly paid to its lead performance, the film fails to accomplish almost everything else it hopes to do. There’s a metaphorical representation of the Wikieleaks site witnessed in the opening credits, an endless business office with shadowed edges and a sand floor, with what’s sure to be hundreds of computers with an assortment of news stories on different monitors. It isn’t an elegant metaphor, and one executed with lackluster production values. For reasons I’m struggling to understand or even identify, the film interrupts the action during crucial “big” moments to return to this venue and seeing the characters interact. This hackneyed attempt at injecting artsy fartsy content into a film lacking any elsewhere represents something much worse than the Wikileaks website, and instead points to the level of misjudged ideas running amok through the film.

Another attempt at flashy visuals comes in the form of heavily digitized opening shots, filled with glitchy pixels and computery static meant to be cute. Ironically, they call to mind an early joke made towards Assange by Bruhl’s Daniel, mocking the hilariously dated graphics in his presentations. That might be okay for powerpoint, but is unforgivable in a major studio movie budgeted at an estimated 30 million dollars. Sure, these two examples are unrelated to the overall aesthetic of the film. But, because they’re both so plainly strange and dated, they harshly clash with the director Bill Condon’s attempt to mimic Greengrass‘ style on the final two Bourne films. Unfortunately, The Fifth Estate never captures the momentum or interest of the many better films it borrows from, and ends up squandering the unique and fascinating true story upon which it is based. So I say fanboy, fanboy hard. Keep your eyes glued to Benedict Cumberbatch from the start of the awkward opening credits ‘till the screen goes dark and you may come out having had a good time. Otherwise, skip it.

C-

A few weeks ago, a wife and her mother were set ablaze in a parked car half a mile from my parent’s home, a rural wooded area that has had nearly zero reported crimes in the last decade. I stood shocked for the whole of ten minutes before tossing it into the ever-growing pile of rotten things that happen, a garbage dump of bad news I started when I had to be 10 years old. I’d catch infomercials for the gaunt starving children in Africa, or hear parents whispering of fatal car crashes, drowned babies in bath tubs, or blood letting firefights in bad neighborhoods. To cope, I created a mental garbage shoot to expel rancid information so these heinous cases could decompose somewhere other than my present, active self. Hearing about horrible things becomes expected, and worse, normal. Atrocities become comfortable the longer they sit with us, and news of bombings and tremendous death tolls become an irksome poke to our principles, rather than an inciting fist slamming outrage. Art and cinema exploit this by using our universal nonchalance against us, confronting viewers with society’s bloody laundry. In 1993, Steven Spielberg released his opus Schindler’s List, testifying to the depravity of Nazism as definitively as any film likely ever will. In 2013, British filmmaker Steve McQueen assembled a star laden production, with Brad Pitt, Paul Giamatti, Benedict Cumberbatch, Michael Fassbender, Hans Zimmer, and star Chiwetel Ejiofor, to attack slavery with the same unflinching veracity Steven Spielberg brought to Schindler’s List twenty years ago. 12 Years a Slave is a gutting experience, making the actuality of slavery in America so palpable, that by the film’s end I was laid bear in the cineplex, exhausted and despondent at a history that has never felt so real.

12 Years a Slave finds McQueen at an artistic high, and a clear mastering of the style he experimented with in Hunger and Shame. Both films featured too many unnecessary long takes, self-indulgently spinning meaning into moments without any. His flamboyant style ultimately undermined his goals, but not enough to stop either film from becoming the dramatically potent works that they are. In 12 Years, he welcomes more conventional (or commercial) aesthetics, but when accompanied by the many perfectly timed stylistic flourishes, they mix into an arresting cocktail. Shots that begin as abstractions of shapes and light refocus to reveal plantation woodland, and plainly lit medium shots are sometimes cut with expressive images of ultra-close ups, beautifully balancing artistic flair with orthodox film language. The cinematography is often this lyrical, and oppresses characters into their environments, whether those are slave auction houses or a farm yard. Some way into the film, there’s a shot epitomizing this idea, where the slaves are in crystal clear focus in the mid-ground, but both the overseer cavalry in the background and cotton plants in the foreground are out of focus. Cinematographer Sean Bobbit lights the film’s meticulous compositions with dignified control, and an oscar nomination is a certainty.

Speaking of oscars, the cast is destined for at least one golden statue between them, and three leads in particular would be deserving. Fassbender’s Edwin Epps is a villain of many shades of black, showing him as a multiplicity of evil instead of typical searching for a lost humanity. Ejiofor’s lead performance as Solomon Northup demands playing contradictions simultaneously, restraining his soul and body from despair while showing the festering spirit of his heart. It’s a devastating performance, and it’s easy to see him walking away with best actor come 2014. These powerhouse performances know when to linger on high-emotion and when to pull away, something McQueen replicates masterfully in his filmmaking. Beatings, hangings, and other forms of physical assault never become an over dramatized focal point, instead prudently spacing them across the running time when appropriate and necessary. This allows us to exponentially empathize with Solomon on his trek through slave country, and our built up investment in the narrative pays off cruelly in a whipping sequence captured a single take that left the theater in tears. Composer Hans Zimmer gives significant bite to these depictions, ratcheting up tension with industrial and abrasive sounds that veer towards experimental. The score would compliment the film perfectly if not for the utterly distracting similarity to Inception's emotional cues, which play under many of this film's most moving scenes.

McQueen discovered an unspeakable power in the story of Solomon Northup, and his stroke of genius inspiration to adapt this story in this way has resulted in the ultimate cinematic depiction of American Slavery, justly due for reverence and adoration in the coming channels of film history.

A+

After having seen Blue is the Warmest Color at the Chicago International Film Festival, I’ve found it increasingly distressing how the some of the American Press has red tagged the film as little more than a pornographic male fantasy of sexy lesbians screwing around. The media, on the hunt for a headline with a hook, unforgivingly obscures the artistic merits of a movie, trading credibility for sensationalism. Director and writer Abdel Kechiche actually touches on this problem in his new film, albeit in an indirect way, where the characters played magnificently by Léa Seydoux and Adèle Exarchopoulus stand infuriated at the commercialization of art. In fact, there isn’t much about social politics, art, and love, that Kechiche doesn’t incorporate into his tapestry of tangled desires.The characters often foster these ideas openly on screen, and lends the film a naturalism in confronting them few films can afford. Look at the blue haired Emma’s family, who represent the Intelligencia, an elite class of peoples that are the purveyors of both culture and the arts. This gives Emma a sturdier boat than most to pursue her ambitious artistic goals, one Adèle’s pragmatic family couldn’t ever give her. By having these ideas animated through the characters, the meaning behind the ideas and characters both deepen, making the film a series of tableau right out of a Jean-Luc Godard, with characters thinking about what it means to live.

We get to know these girls better than our coworkers, classmates, roommates, or best friend. These are intimate portraits cultivated with a clear sense of duty and love to their work, where honesty is paramount. At some point you have to ask yourself, is playing the voyeur to these women pleasuring one another any more intrusive than standing beside them in the trenches of their most brutal and devastating fight? Yes, this film has extremely graphic sex sequences. They are long, they are tantalizing, and they are as erotic as anything put to film. They also serve a grander purpose beyond viewers sharing the emotional whirlwind of Adèle and Emma’s relationship.

Constantly, people try to connect. Sometimes, that’s through sex, but far more often, that’s through food. More specifically, sharing a meal. In almost every moment of emotional bonding, characters are eating, like the awkward first date with a boy from school, or family dinners. Food and sex are used similarly, either bringing people together, like Adèle popping turkey slices into her mouth at the park, or driving them apart, like the dinner party with Emma’s friends. In this way, food and sex are catalysts towards revealing who does or doesn’t work with whom, or in other words, their chemistry. It’s an intelligent and subtle tool for Kechiche to use, and I applaud him for it.

While Lèa gives a tremendously layered performance, unknown actress Adèle is a revelation. She anchors a film always moving in many directions back right to her, and delivers an emotional powerhouse of a performance playing a character of extraordinary nuance. Adèle, the character, all about the wholeness of feeling, and rebels against professor’s over-intellectualizing a work. Analyzation cripples the imagination, she says, and she sustains her opposition until the credits roll. She struggles with the niceties of philosophy and giving clarity to why she loves a thing. It just isn’t who she is, and while it might be easy to call her simple minded because of it, the intricacy of her feeling overwhelms her mental competences. She can feel great works of art with complete satisfaction without ever backpedaling formulated responses for what gives a thing resonance. She’d call that, and probably this review, bullshit. She internalizes, and she even fiercely resents sharing her skillful writing with more than a diary. She makes these character traits crystal clear very early in the film, and allows no room for ambiguity. For her, these are absolutes kindred to her way of being, or her essence, and they resurface constantly, but especially whenever she has to describe a painting.The movie makes a big deal out of the dichotomy of what’s basically nature vs nurture, using the debate between the two as a core propulsion to the inner-engines of the film. That’s important to understand, because Adèle’s essence, or nature, has no tether to the world Emma hopes she’ll enter. She can’t join dinner party discourse on high art theory, and as a result feels alone. Blue is the Warmest Color is film of characters in constant debate over their ideas and convictions, even if it's so submerged in their natural behaviors and conversations they aren't even aware that's what they're doing.

Kechiche gathers universal experiences and pushes them under vicious scrutiny, and I found my own person within the turbulent turns of the story more than I'd have liked. It's with the highest compliment I can say I suspect many, probably even most, of the few hundred people sharing the theater with me Saturday night would agree. Blue is the Warmest Color is a startlingly raw depiction of modern love, and these are only a selection of the reasons why. To unpackage three hours worth of filmmaking this good, this complete, would take many multiple viewings and personal reflection, and for me, that is an absolute treasure.

A+

I am not a fan of Sandra Bullock. She brings the same stirred up angst to almost every role, which almost always ends with yelling or being an aloof moron. Interestingly, Director Alfonso Caurón continued this trend in Gravity, and also cast his second lead under similar circumstances, with George Clooney playing a caricature of the George Clooney pretty much everybody loves, but especially my mom. Maybe the studio saw the film as a colossal risk, an economic expenditure with a risk of a low-yield, so they pushed the most traditional and wide-release friendly faces they could find into the title roles, front and center, to support the risk. That's been the narrative surrounding the film's production for years. The alternative, and this isn't mutually exclusive with the first option, is that Cuarón is a clever bugger and saw the persona of these two lead actors as essential to communicating some tricky ideas as simply as possible.

See, Cuarón is all about the simplest, cleanest, clearest way to present ideas. He resists the temptation to overcomplicate with ambiguous "heady" visual metaphors, or layered mind-bending plots. It's a brazenly unpretentious way to make a movie, and there's a recurring phrase the director keeps repeating in interviews: "Pure Cinema Language." I think I know what he means, and I'm pretty sure his approach to cinema is a blood relative to Hemingway's style in literature—simple, honest prose. In fact, swaths of critics have mistaken simplicity for shallowness, confusing the visceral totality of their experience with the absence of ideas supporting it. Instead, Gravity is an impossible juggling act of complex, contrasting ideas, vying for the limited space the film allows. Therein lies the true genius of the film, not with the effects, not with the digital camera work (both of which are utterly transcendent), but with how Cuarón merges multiple meanings into single symbols. This informed every possible layer of the production, including, of course, casting. George Clooney and Sandra Bullock both bring their acting personas front and center to the roles, with the warm folksy assurance of Clooney's Matt Kowalski pushing up against the contracting anxiety of Bullock's Dr. Ryan Stone. Those traits are human, but like most things in this film, there's a crucial spiritual core guiding these elements of plot, direction, and character.

Kowalski never loses his cool, never loses control, and vitally, never removes himself from the present. He is there, and his past has reduced to a list of charming stories. In other words, he has achieved a state of bliss, where he experiences the moment as he experiences it. In Zen Buddhism, these traits would define him as a Shike, or in American pop culture, a "Zen Master." In Contrast, Bullock's Dr. Ryan Stone is in a perpetual state of loss, with her painful past always around the corner. The characters aren't the only thing used for multiple purposes, so enter, space: a limitless expanse lifting the weight of Earthly baggage into zero gravity, allowing Dr. Stone (and probably us viewers) a tranquility she hasn't ever experienced on Earth. She alludes to this feeling in the film, stating "the silence" of space is her favorite part of a space walk. This makes space is a metaphorical Nirvana or Heaven, and the debris, then, becomes the inevitable confrontation with the unwanted turns of life. Unless you are well equipped to rethink, adapt, and rapidly change trajectory with minor personal consequence, you'll wind up spinning into an endless void of nothingness.

These instances of change take the form of the vessels she has to fix, and the series of cliffhangers that punctuate these moments resemble our last ditch attempts to grab hold of any idea, any behavior, and indeed any person, that might make it okay. These represent several of a multitude of opposing forces coursing through Gravity. Yin and yang. When reflecting on the quantity (and quality) of allegory included in every frame of Gravity, it becomes clear Caurón pursues the question of existential survival every bit as much as its grandaddy 2001: A Space Odyssey did decades ago. With a similar breakthrough of technology that is probably the most poetic and complete use of computer effects to date, the synthesis of film form and film theory is a singular and beautiful experience demanding to be seen on the biggest screen possible. Life, death, rebirth, meditation, evolution, and catharsis— these are the contracting and expanding feelings breathed through the soul of a film destined to become an all time classic.

A+

Captain Philips doesn't reach the dramatic highs of United 93 or the quick cutting intensity of The Bourne Ultimatum, but Greengrass' cine-veritê style has enough punch for Philips to ascend not only as one of the best thrillers of the year, but as one of the best films this year. Philips cleverly opens by following two captains on either side of the globe, each charging up for a mission at sea. Their settings couldn't be farther apart, one from a routine middle class home and the other a filthy hut in a poor island village, but as the opening moments carry on, similarities emerge. The screenplay goes some ways stress these parallels, but like much of the film, we're left with forced dialogue looking to be perceptive. We are told both characters have a boss, both exist in a pre-ordained system in which they have no ultimate authority and where their longevity as people depends on their obedience to this system. Despite the radical difference in background, capitalism has entwined these two men together, like two managers of rival corporations fighting for a career making kill. The capitalist subtext isn't subtle and doesn't pretend to be, but it's the stark direction and performances that helps the dialogue escape harsh comparisons to the opening lecture of your average freshman year sociology seminar. An unforgiving number of key moments suffer from transparent sermon syndrome, and a stronger screenplay would have had Captain Philips standing as a deeply relevant and proactive drama.

But, incredibly, the screenwriting missteps didn't impede the intensity whatsoever. My theater's attendants were still. Greengrass had them by the throat, and the few moments they could take a breath followed immediately with shock and even terror. There's few innovations to his signature style, but it works wonders, especially when cross cutting between the frenzy of charging boats and the lumbering freighter. Though there's never any doubt who the villains are, the constantly emphasized semblance between the two captains thickened the drama immensely. Because each character has been painted as a victim, most characters are treated in an uncomfortably effective sympathetic light, causing viewers to care about the "evil" hijackers more than the conventional film might have allowed.

Adding to the forceful tension gleaned from the one-false-move-and-you're-done-for maneuvering around the massive freighter, these elements of nuance forge a singular air of suspense that's frankly missing in the majority of studio movies. Tom Hanks gives one of the best performances of his career that escalates tension further still: it's a masterful balancing act between asserting control into a situation that doesn't have any, and constantly coming close to pushing too far. If for none other reason than the raw emotion Hanks sells in the third act, this man deserves an oscar nomination, and probably will get one. While no single element stands out as a 'best in show' for this year's best example of bravado filmmaking, the excellence found within Captain Philips' tough execution is so high, it will find no problem ranking high on end of year best of lists.

B+

For all the Christian iconography and focus on myth building, you'd hope the filmmakers learned something about hubris. They didn't. Pure ambition consumes every level of the film-- the duration spent on Krypton, the godly scale of most action sequences (that on the first go round mastered almost everything Marvel's ever tried to accomplish with action scenes), that it has an awful lot more in common with E.T., Independence Day, and Avatar rather than Iron Man, but the biggest gamble was deciding Clark Kent doesn't need much of a character arc. Typically this might mean a hollowness to character development, but by bifurcating past and present as Goyer has, it necessitates that the viewer comes to understand Clark as he is rather than watch him grow and develop as a character. For the first half of the film, he remains an enigma that, for me, made it a struggle to care. The times spent on the farm are often powerful despite being wildly cliche, but the editing from scene to scene and even shot to shot was, well, a mess to the point where every moment I'm pulled in, some perplexing editing choice pushes me right out. A more linear narrative would have helped, but because the editing issues extend to cutting between bars, streets, farms, interrogation rooms, and military compounds, we may have been left nearly as puzzled.

Clark marches on as an unknowable bearded guy with a perfect physique that finds himself in more disaster scenarios than John McClane. However, Lois Lane has a great line of dialogue explaining why they kept him on the peripheral. He's unknowable precisely because that's all he was then to mankind. Us, as well as to her. She's our Watson to Clark's Sherlock, and the more they're on screen together, the more connected to Clark we become. From this point on, we come to know Clark more intimately, although he's often too busy employing a hundred employees at Weta to remember he's a character. Weirdly, critics saw the fireworks and apparently reacted by dismissing any depth or themes they came across. For instance, Lois is a surprisingly active protagonist in a genre often doomed with brainless sexist caricatures. She bravely thrusts herself into the forefront of danger for the greater good, and the criticism she becomes a simple damsel in distress is nonsense. Additionally, Clark faces a series of colossal decisions during the last half involving 'his people' that hang on the guidance we've seen his parents bestow upon him, bringing full circle the time spent with them. There's some interesting things going on here ethically, and that doesn't change throughout the film. All of his parents (and Lois) are highlights, and bring warmth to a film so engulfed in blue. Unfortunately, the whole cast isn't up to par. Some actors can chew through stilted dialogue, and Michael Shannon is not one of them, and while Zod and his ferocious sidekick may be far above most Marvel villains, they don't touch Nolan's vision of the Rogue Gallery.

Man of Steel is a confused film, and that's largely due to biting off a lot more than Zack or Goyer could chew. For all the intelligence, occasional depth, and the creativity brought to some truly mind blowing set pieces, it struggles with a perplexingly poor narrative structure that leaves viewers cold in a film full of warm moments. Some huge moments are awkwardly rushed, and it's grumpy cat atmosphere damages the hope it constantly spouts having. But, it's earnest, bold, and elevated by a wonderful score that perfectly captures this iteration Superman. With a better script and director, this had a shot at being something special-- a genre bending alien invasion superhero masterpiece. However, the arrogance that they could pull something this daring off without damaging the integrity of their film leaves a bad taste in my mouth, even if I really did enjoy the flavor.

There's an emerging trend amongst film critics to cry out at the new studio fetish to hold a competition over which summer blockbuster can include the darkest materiel and cause the most wanton destruction. It might not be entirely unjustified, hardly a blockbuster this year met the credits without an uneven balance between dark and light, usually tipped in favor of not fun. It's then ironic that the underdog contestant of the summer is the one to master everything no other film this summer succesfully could. Just as the world's biggest powers pooled resources to defend the Earth from monsters, Pacific Rim gathers the best archetypes and tropes from a various set of sources around the globe. As a friend pointed out, the fallen hero on a path to regain honor is a classic American Western storytelling trope. However, the second lead, an asian girl named Mako, features a past and personality familiar to anyone with exposure to Japanese manga or anime. While these are well-worn conventions within their respective cultures, both critics and viewers seem to miss that rarely have they been brought together with such effortless flare. Thus, not only does the international cast and world-wide participation give viewers a sense of stakes and community, but there's something uniquely powerful about including these archetypes that work together so flawlessly as the only measure to defeat these epic foes.

Employing his skill-set from past films, Del Toro's world-building is so organic, he makes including the Kaju's effects on religion, the black market, and the psychology of the warrior so easy it may have even been easy to miss. There's another explanation to the liquid ease on display: the filmmakers have a heavy foot on the gas pedal, and the film absolutely flies by. This is especially the case in the second half, which is a nearly nonstop onslaught of battle that re-write the modern blockbuster definition of epic. Arguably, Pacific Rim features as many cgi-filled action sequences as Man of Steel. However, where Man of Steel exhausted viewers and sometimes bored them, Pacific Rim grounds them in reality with extremely well assembled action photography and editing, wisely employing traditional camera placements and movements to create a sense of needed realism juxtaposed to the fantastic. Because of this, the action feels grounded, and each blow actually impacts the audience. To keep viewers invested before the jaw-dropping Hong Kong set piece (probably the best of the summer), there's a compelling interplay between the melding of each pilot's mind and the control of a Jaeger, and I wish more screen time was devoted to this plot strand, especially as the final act turned its head. The performances are wildly uneven, some imbuing a necessary sense of humanity into the above described scenes, others a rude distraction in an otherwise cohesive film. Unsurprisingly, Idris Elba's flippin' fantastic, and probably had the best materiel to work with on a script level. It should also probably be noted the two bumbling scientists will either strike viewers as abrasive or really fun, but I saw them more as a clever way to diversify storytelling, and to that end they were successful.

That's not to say the film doesn't have flaws: The best ideas are the ones with the least screen time, the performances mostly range from bad to serviceable, the final set piece can't compare to the one taking place in Hong Kong, and the script is surprisingly poor on the easy stuff. By that I mean the screenwriters seemed so busy getting everything right nobody else could. Notably two things: a certain plot element turns out to have absolutely no bearing on the narrative, but to say which or why would be considered a spoiler, and the 'motivation' behind the attacks. While not a flaw, I'm also shocked how literal the film borrows from hard-core science fiction and anime, and I fear this may alienate some audiences. All that said, Pacific Rim triumphs where most films this summer have failed, masterfully balancing not only dark and light with a pervading sense of glee, but by also balancing aesthetics and narrative tropes from international adventure storytelling. This is a film for the world from the heart of a very mature and intelligent teenage boy, confident and proud of the story he wanted to tell. I loved it!

B

Park borrows, returns, and alters classic genre tropes to tantalize and provoke viewers, however I'm uncertain his ends ever form a complete picture. To his credit, the more I sit on it, I'm not sure they were meant to. Train tracks serve as a vintage euphemism for the criss-crossing of a confused identity, as well as the burgeoning eroticism experienced by at least one of the three leads. Characters exist in sexual claustrophobia and search for a key to unlock it, which, as the film unfolds, viewers learn can take many fucked-up forms. They just want to get off.

The usual suspects are mostly worth investigating, and while the screenplay succesfully serves as a vehicle for Park using it's thin narrative for fetishizing gothic cinema, I can't help but think it never should've tried to break out of prison (I had to). Had the screenplay been fleshed out and written by more capable hands, Stoker would've been in my top five of the year. As it stands, it'll likely gain status on my end of the year list, but only because of the unapologetically twisted-- and brave-- nature of the filmmaking and performances on display, though it occasionally feels a little silly or contrived simply because of how thin it is.

The worst thing I can say about Stoker is that had I seen it in high school, I would've fallen in love. Luckily, Park and his fantastic cast elevates it into a delicious experience likely to stand as one of the most memorable this year, even if not the best. Because the film itself is so fractured and disjointed, this review probably ended up just as so. I wish it got better reviews, it deserved a lot more.

Outstandingly lacking humility, it's a cocky film, seemingly sure in its ability to capture the expanse of time and consequences through a revolving door of visual and auditory motifs, not to mention Cianfrance's insistance on single takes. Essentially, the first forty-five minutes to an hour--somewhere in there-- are cinematic majesty, virtually achieving everything anyone on this project hoped to accomplish. Surprising tenderness is juxtaposed with the art-house equivalent to high-octane chase sequences, and along with the robberies seen in the trailers, they continually kick you in the gut. At times, this can produce an overwhelming effect in a rich and highly involving manner, enhanced all the more by a catalogue of creative cinematography, from the carnival lights to the dizzying camera following Luke in a forest full of pines. Gosling is magnetic, offering what may have been his best performance to date, or at least amongst the very best- he's an emotional powerhouse through a multitude of acting subtleties, and had this film been released closer to bullshit statue time, he may have had a serious shot at a win.

Unfortunately, the sinister whimsy dominating the tone, characters, and more or less, life, in this opening act quickly dissipates in exchange for a routine plot template in countless films and tv shows, but to be fair, Cianfrance tells these stories with rare lyricism and thematic density, articulated beautifully in a speech given some ways through by Bradley Cooper- who's also fantastic. Especially memorable is a dinner scene with emerging anxiety from each of the characters-- none can truly claim complacence. But, for me, the artistry present in every turn of the first act is rare to be seen throughout the second act or even third act, returning (admittedly rather spectacularly) in the final fifteen or twenty minutes. The cinematography becomes a dour affair, and not even the grace written and directed into these scenes can always elevate it beyond conventionality. Without talking much about it at all, this is most evident in the final act of the film, where key new characters are merely finely executed stock archetypes witnessed constantly in a few different genres, and for those that know where the film is headed can infer which I mean. Worse still, the film isn't even rushed in the sense several scenes feel written into one, but instead feel as though an index of importnat scenes were omitted completely. Without being too specific, it becomes a challenge to constantly stay at the emotional high the film clearly thinks it deserves. In large part, this is due to the radical changes in plot and character motivation that happen unnervingly frequently- it's not that these actions aren't believable, they are, it's that the film never breathes long enough to let our spongey hearts fully absorb the drama before moving on to another plate of tragic storytelling.

I'm confident some of this reaction was deliberate, specifically that the poetry and power felt in the first act was meant to echo throughout the remaining minutes, especially because it establishes the many motifs used sporadically throughout. It's just that the film never stops sprinting to greatness, but constantly using the first act to drive the key emotional moments throughout obstructs Pines from ever running past the first act's shadow. Running and running, it seems to always get out of breath just as it has you convinced it just might cross that shadowy threshold. It doesn't. Ultimately, it fails as an attempt to emulate Shakespeare and Greek Tragedy in equal measure, and not a second passes without it being exceedingly (and distractingly) obvious that Cianfrance thinks he's made a masterpiece. The thing is, if the artistry and attack on the ordinary that perseveres through the first act continued, he may just have. As it stands, The Place Beyond the Pines is deeply flawed but harrowing and haunting plunge into the poisoned legacies of our fathers. It is never less than a beautiful and stirring piece of cinema that's chased me ever since the credits rolled, and although that doesn't make it a masterpiece, it is an ardent declaration of the film's transcendent power.